Sarah spent parts of her the weekend documenting her current scheduling process as Emma had requested as input for their scheduling software selection. She mapped out every step, every decision point, every workaround she used daily. The document ran to twelve pages and made painfully clear just how much tacit knowledge and intuition went into what looked like simple whiteboard management.

But as she worked on the documentation, another idea took shape. If they were going to evaluate scheduling software, shouldn’t they approach it systematically? Sunday evening found her creating a comprehensive feature matrix spreadsheet—armed with software selection guides she’d downloaded and a determination to approach this decision methodically.

Monday went without any surprises, and then the day of the first production scheduling software selection workshop came.

Tuesday morning found the core team—Emma, Klaus, Patrick, Otto, and Sarah—gathered in the conference room, along with Jenny and Mike from assembly. Marcus and Henning sat at the back, observing. Sarah had sent everyone her scheduling process documentation the day before, but now she shared something different.

“I’ve created a structured approach,” Sarah explained, projecting her spreadsheet onto the screen. “We’ll categorize every feature as ‘must have,’ ‘good to have,’ or ‘nice to have.’ This will give us an objective framework for evaluating different scheduling software options.”

The spreadsheet was impressive—color-coded rows, dropdown menus for priority levels, columns for notes, and justification. It looked exactly like the kind of professional tool that would lead to rational decision-making.

“I like it,” Klaus said. “Let’s start with the must-haves. Obviously, we need finite capacity scheduling.”

Sarah typed “Finite Capacity Scheduling” into the first row and set the priority to “Must Have.”

“What exactly does that mean?” Otto asked from the back of the room.

Klaus looked surprised by the question. “It means the system considers that we have limited machine capacity.”

“But how does it consider it?” Otto pressed. “Does it just tell us when we’re over capacity, or does it automatically figure out a different sequence?”

The room went quiet for a moment as people realized they weren’t entirely sure.

The Definitional Debate

“Let me look up the technical definition,” Patrick said, typing on his laptop. He read from a software vendor’s website: “Finite capacity scheduling is a planning method that schedules production orders based on available capacity constraints, ensuring no resource is over-allocated.”

“That’s not very helpful,” Jenny muttered.

Sarah tried to clarify. “I think it means the software knows how much capacity each machine has and won’t schedule more work than fits.”

“But that’s obvious,” Mike said. “Isn’t that just basic scheduling? Why would you schedule more than you can do?”

“Business Central does that,” Klaus pointed out. “It schedules based on when things need to be done, not whether we have capacity.”

“So we’re saying we need software that’s smarter than Business Central about capacity,” Sarah said, trying to synthesize. “Should I mark finite capacity scheduling as must have?”

“Wait,” Otto interjected. “If the software knows we don’t have capacity, what does it do? Tell us we can’t do the job? Move it to a different day? Use a different machine?”

Everyone looked at each other, realizing they were already stuck on the very first feature.

“Maybe we should define what we mean by each feature before we prioritize them,” Patrick suggested.

“Good idea,” Emma said. “Sarah, let’s add a column for definition.”

Sarah added a column labeled “What This Means.” The first row now read: “Finite Capacity Scheduling | Must Have | [What This Means]”

“So how do we define finite capacity scheduling?” she asked the group.

The room erupted into overlapping explanations. Klaus talked about capacity constraints. Patrick mentioned work and machine center calendars. Otto described how they currently manage capacity manually. Jenny wanted to know if it covered people’s capacity or just machines.

Twenty-five minutes later, they had a paragraph-long definition that no one was completely satisfied with, and they hadn’t even moved to the second feature.

The Setup Optimization Argument

“Let’s move on,” Emma said, glancing at her watch. “Klaus, you mentioned setup optimization earlier. That’s on your list, right, Sarah?”

Sarah scrolled down her spreadsheet. “Yes—sequence-dependent setup time optimization. I have it as ‘good to have.’ Klaus, did you want to argue for must have?”

“Absolutely,” Klaus said, leaning forward. “We waste enormous amounts of time on setups. If we could batch similar jobs together, we’d significantly increase the productivity of the respective machines at that stage. That directly impacts our costs and efficiency.”

“Hold on,” Otto said, his voice carrying a note of warning. “You want to batch jobs together? What about delivery dates?”

“We’d still meet delivery dates,” Klaus replied. “We’d just organize the sequence more efficiently.”

“Klaus, every time we try to batch things for efficiency, we end up making customers wait longer,” Otto said. “Remember last month when we grouped all the steel jobs together to minimize material handling? Three customers called complaining about delays.”

Klaus frowned. “That’s because we didn’t do it properly. With software managing the optimization—”.

“Software doesn’t talk to angry customers,” Otto interrupted. “I do. And I can tell you that customers don’t care if our setup times are optimized. They care about getting their parts on time.”

“But if we’re more efficient, we can deliver more jobs on time,” Klaus countered.

“Or we can focus on delivering the jobs we have on time instead of trying to squeeze in more,” Otto shot back.

Sarah found herself caught in the middle, literally—Klaus sat to her left, arguing for efficiency, Otto to her right, arguing for responsiveness. “Guys, let me ask a question. How much time do we actually spend on setups related to the entire runtime of a job?”

Klaus pulled up his notes. “Setup times are just crucial in precision machining when it comes to tool changeovers and restarting the machine with a few test runs. According to my analysis, here the setups average about twenty to thirty percent of our total machine time.”

“And how much is this related to a typical entire job?”, Sarah asked.

Klaus scratched his head. “My gut tells me that this might be around 10% of total runtime maximum.”

“O.K., and as much as I know from our whiteboard, precision machining typically isn´t a bottleneck. Then, colleagues, my impression is that we have a bigger issue than minimizing the costs of this stage.” Patrick looked at his laptop and added, “I’m reading about setup optimization here. It says ‘ideal for high-volume repetitive manufacturing with stable demand patterns.’ Does that sound like us?”

The room went quiet again.

“We’re high-mix, low-volume,” Sarah said slowly. “Our demand changes weekly. We don’t really have stable patterns.”

“So maybe setup optimization isn’t as critical as I thought,” Klaus admitted reluctantly. “Or maybe it’s situation-dependent?”

“How do I capture that in the matrix?” Sarah asked, staring at her spreadsheet.

The Complexity Cascade

“Let’s park this for a moment and move to the next one,” Emma suggested. “What about visual scheduling? That seems straightforward.”

Sarah created a new row: “Visual Scheduling Interface | Must Have”

“Wait,” Patrick said. “What kind of visual interface? Gantt chart? Kanban board? Calendar view? Dispatch list?”

“Gantt chart, obviously,” Klaus said.

“Why obviously?” Jenny asked. “I find Gantt charts confusing. Too many bars and lines. I prefer a simple list of what needs to be done next.”

“But Gantt charts show you everything at once,” Klaus argued.

“That’s the problem,” Jenny countered. “I don’t need to see everything. I need to see my next three tasks.”

“Those are different user interfaces for different purposes,” Patrick explained. “Schedulers need Gantt charts. Floor supervisors might need dispatch lists. We’re actually talking about multiple features.”

Sarah stared at her matrix. “So do I add separate rows for each view type? Or one row that says ‘multiple view options’?”

“What’s a Gantt chart anyway?” Mike asked.

Klaus looked shocked. “You don’t know what a Gantt chart is?”

“I know what a schedule is,” Mike replied defensively. “I just don’t know why you need a fancy name for it.”

“A Gantt chart is a bar chart that shows tasks over time,” Patrick explained.

“So why not just call it a bar chart schedule?” Mike asked.

They spent the next 15 minutes explaining various scheduling visualization methods, only to discover that team members had completely different ideas about what “visual scheduling” meant.

The Two-Hour Debate

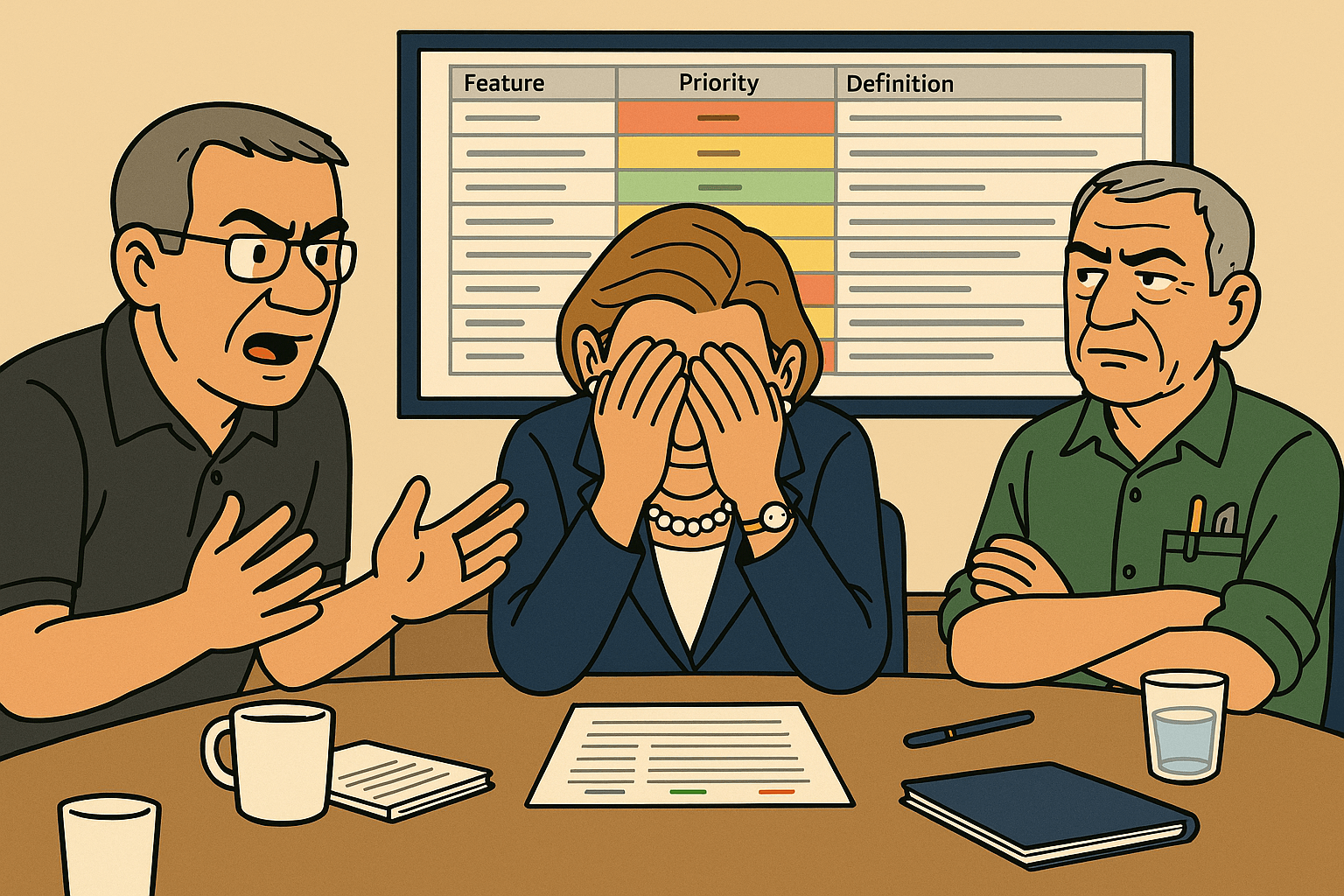

By 11 AM, they’d been working for two hours on their scheduling software selection and had defined only five features, each with extensive notes, caveats, and unresolved questions. The conference room had taken on the atmosphere of a philosophy seminar rather than a practical business meeting.

“Let’s tackle something simple,” Emma said, a note of desperation creeping into her voice. “Drag-and-drop functionality. Surely we can agree on that quickly.”

“Definitely must have,” Klaus said.

“Good to have,” Otto countered.

Everyone turned to look at him in surprise.

“Otto, why would drag-and-drop be anything less than must-have?” Sarah asked. “It’s the most basic feature of scheduling software.”

“Because I don’t want people dragging things around without thinking,” Otto replied. “Last week, you spent two days figuring out that weekend schedule. If you’d had software that let you drag things around easily, you might have made changes too quickly and missed something important.”

“That’s an argument for training, not against drag-and-drop,” Klaus said.

“Is it?” Otto asked. “Or is it an argument that easy changes lead to careless changes?”

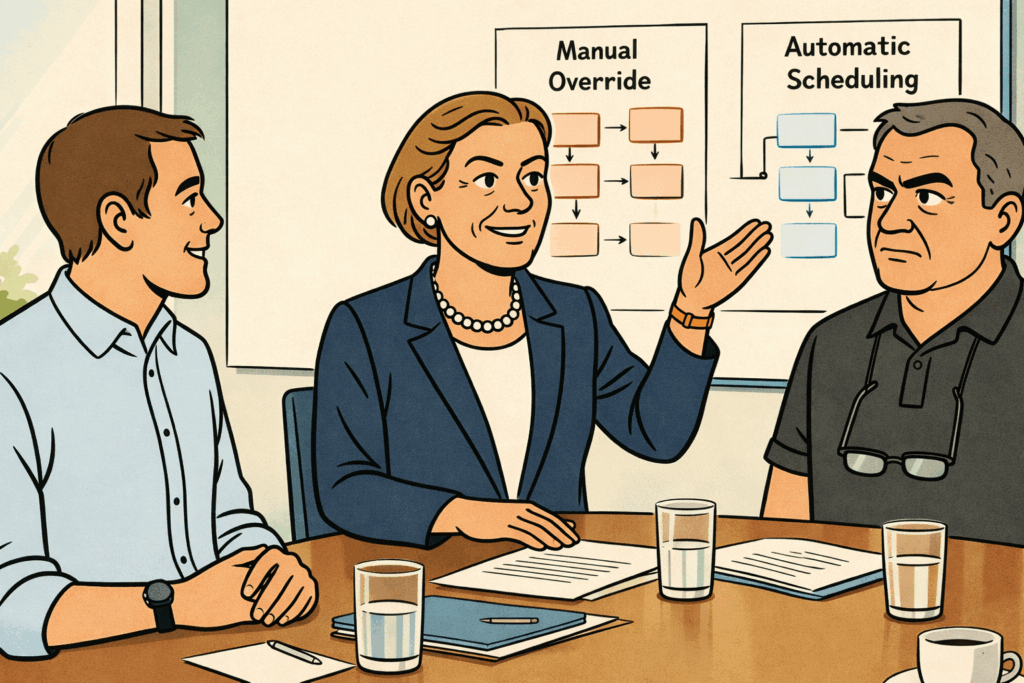

Patrick jumped in. “Actually, Otto raises an interesting point. Some systems allow unrestricted drag-and-drop—you can move anything anywhere. Others have intelligent drag-and-drop that won’t let you create impossible situations. Which do we want?”

“Both,” Klaus said.

“They’re opposites,” Patrick replied. “One gives you complete freedom. The other constraints you to valid moves only.”

“Then we want the one with constraints,” Sarah said. “We don’t want to create invalid schedules accidentally.”

“But what if the constraints are wrong?” Otto asked. “What if the system thinks something is impossible, but I know from experience it can be done?”

“Then you’d need an override function,” Patrick said.

“So we want constrained drag-and-drop with an override option?” Sarah asked, trying to keep up.

“Yes,” Klaus said.

“No,” Otto said simultaneously.

“Why no?” Klaus asked, exasperated.

“Because if people can override the constraints, what’s the point of having constraints?” Otto explained. “We’re back to unrestricted drag-and-drop, just with extra steps.”

Emma put her head in her hands. “Are we seriously debating the philosophical implications of drag-and-drop functionality?”

Why Feature Matrices Can Fail for Scheduling Software Selection

From his seat at the back of the room, Henning had been watching the proceedings with an expression that had evolved from interest to concern to something approaching alarm. He finally raised his hand.

“May I offer an observation?” he asked quietly.

“Please,” Emma said. “Anything to break this loop we’re in.”

Henning stood and walked to the whiteboard. “I’ve been counting. In the past two and a half hours, you’ve fully defined five features, partially defined eight more, and created seventeen new questions that you didn’t have when you started.”

He drew a simple diagram on the board. “Here’s what I’m seeing: You’re trying to build a feature matrix without understanding what the features actually do in practice. It’s like trying to order food at a restaurant in a language you don’t speak. You can point at items on the menu, but you don’t really know what you’re going to get.”

Sarah felt a flush of embarrassment. Her beautiful spreadsheet, which had seemed so professional and scientific, was actually exposing how little they understood about what they were trying to evaluate.

“Give me an example,” Klaus said, sounding defensive.

“Setup optimization,” Henning replied. “You spent twenty minutes debating whether it’s a must-have or a nice-to-have. But the real question isn’t the feature’s priority—it’s whether your manufacturing environment benefits significantly from setup optimization, or only marginally. And you can’t answer that without understanding how setup optimization actually works, what it optimizes for, and what trade-offs it requires.”

He pointed to another row in Sarah’s spreadsheet. “Finite capacity scheduling—you spent fifteen minutes trying to define it. But there are multiple approaches to finite capacity scheduling. Forward scheduling, backward scheduling, constraint-based scheduling, optimization-based scheduling, and more. Each approach handles capacity differently. Until you understand these approaches, how can you evaluate whether a system does it well?”

The room was quiet now, everyone recognizing the trap they’d fallen into.

“Are you saying our feature matrix approach is wrong?” Emma asked.

“I’m saying it’s premature,” Henning replied. “Feature matrices are useful when you understand what you’re evaluating. But right now, you don’t have a shared understanding of what scheduling is, how it works, or what different approaches exist. You’re trying to scientifically evaluate something you can’t yet describe precisely.”

The Illusion of Objectivity

Henning walked back to the screen showing Sarah’s elaborate spreadsheet. “This looks very professional. Color-coded. Structured. Objective. But it’s creating an illusion of precision. When you can’t even agree on what ‘drag-and-drop’ means, how can you objectively score systems on whether they have it?”

“So what should we do instead?” Sarah asked, feeling deflated. She’d worked hard on this framework.

“First, you need to understand scheduling itself,” Henning said. “Not software features, but scheduling as a discipline. What are you trying to accomplish? What are the different philosophical approaches? What trade-offs exist in job shop environments like yours?”

He picked up a marker and wrote on the whiteboard: “What is scheduling?”

“It’s assigning jobs to machines,” Klaus offered.

“And people,” Otto added.

“At specific times,” Patrick said.

“In a sequence that works,” Sarah finished.

Henning wrote all of this down. “Okay. And what makes a sequence ‘work’?”

“It meets delivery dates,” Klaus said.

“It uses resources efficiently,” Patrick added.

“It’s adaptable when things change,” Sarah said.

“It’s actually possible to execute,” Otto contributed.

Henning stepped back from the board. “Notice how those four things might conflict? Meeting delivery dates might require inefficient resource usage. Efficiency might reduce adaptability. Optimization might create sequences that are theoretically perfect but practically impossible.”

He turned to face the group. “Until you understand these trade-offs, you can’t intelligently evaluate software. You’ll be comparing features you don’t understand to solve problems you haven’t clearly defined.”

The Realization

Emma stood and walked to the whiteboard, studying what Henning had written. “So we’ve spent three hours trying to be scientific and objective, but we’ve actually just been creating an elaborate way to be confused?”

“That’s a harsh but accurate assessment,” Henning said gently.

“What I’m hearing,” Sarah said slowly, “is that we need to back up. We need to understand what we’re trying to accomplish before we can evaluate tools to accomplish it.”

“Exactly,” Henning confirmed. “You need to understand what scheduling means in your environment. What is really crucial for scheduling in your use case, and what can be neglected. Then see which approaches exist, what each is good for, and what it’s not good for. Then—and only then—can you meaningfully evaluate software for your particular use case.”

Klaus closed his laptop. “I thought we were being so systematic. Turns out we were just being systematically confused.”

Otto actually laughed. “Klaus, this is the first thing you’ve said all day that I completely agree with.”

“So our feature matrix is useless?” Sarah asked, looking at her elaborate spreadsheet.

“Not useless,” Henning said. “Just premature. We’ll come back to it eventually. But first, we need to build your team’s understanding of what you’re actually trying to buy.”

Emma checked her watch. “It’s almost noon. Let’s break for lunch. Henning, can you stay this afternoon and help us understand what we should have learned before we started this process?”

“That’s exactly what I was hoping you’d ask,” Henning replied.

The Lunch Break Revelation

Sarah grabbed her lunch and headed to the quiet courtyard outside the building, needing some fresh air and space to process what had just happened. She pulled out her phone and saw a text from Miguel from an hour ago: “How’s the big requirements workshop going? Very scientific and professional, I’m sure 😊”

She almost laughed at the timing. “Not quite as planned,” she typed back. “Turns out we were trying to evaluate software without understanding what we’re evaluating. Spent 2 hours debating drag-and-drop philosophy.”

Miguel’s response came quickly: “That sounds very German. Very thorough. Also very you. 😄”

“What do you mean ‘very me’?” she replied.

“You like to organize and categorize things. Remember when you spent a weekend reorganizing Tom’s toys by size, color, AND function?”

Sarah smiled despite herself. “That made sense. Blocks with blocks, cars with cars.”

“Tom couldn’t find anything for a week because he didn’t organize them the way you did,” Miguel texted back. “Sometimes you can over-organize. Sometimes you just need to play with the toys and figure out what works.”

She stared at the message, struck by how perfectly it captured what had just happened in the conference room. They’d been trying to organize and categorize before they understood what they were organizing.

“You’re annoyingly wise today,” she typed.

“It’s my natural state. See you tonight. Tom wants to show you his new football move.”

Sarah thought of her elaborate spreadsheet. All those carefully defined rows and columns, all that color-coding and structure. It looked so professional, so objective, so scientific. And it had led them absolutely nowhere except into debates about the philosophy of drag-and-drop.

Henning was right. They needed to understand the particularities of scheduling in the Alpine environment before they could productively evaluate scheduling software. They needed to play with the concept before they could organize it.

The Afternoon Reset

When the team reconvened after lunch, the atmosphere had shifted. The defensive energy from the morning had given way to something more open and curious.

“Alright,” Emma said, “Henning, you have the floor. Teach us what we should have known before we tried to create that feature matrix.”

Henning smiled. “I appreciate your openness to starting over. What I want to do this afternoon is help you understand scheduling not as a list of features, but as approaches to a problem. Once you understand the approaches, you’ll be able to evaluate whether specific software supports the approach that fits your needs.”

He cleared the screen and pulled up a new presentation. “Let’s start with a simple question: What are you actually trying to do when you schedule production?”

“Assign jobs to resources,” Klaus said.

“At specific times,” Patrick added.

“Good,” Henning said. “Now let me ask a more interesting question: Do you want to find the best possible schedule, or do you want to find a good schedule quickly?”

The room was quiet as people processed the question.

“What’s the difference?” Otto finally asked.

“The best possible schedule might take hours to calculate,” Henning explained. “A good schedule might take minutes. In an environment like yours, where things change constantly, which is more valuable?”

“A good schedule quickly,” Sarah said, thinking of her weekend ordeal.

“Exactly. And that choice—optimization versus speed—is more important than any individual feature. It’s a philosophical difference about what scheduling should accomplish in your environment.”

He advanced his slide. “Let’s talk about what this means for your software selection. But this time, instead of features, we’re going to talk about fit.”

As Henning began explaining scheduling philosophies and approaches, Sarah realized they were finally asking the right questions. Not “What features do we want?” but “What are we actually trying to accomplish, and what approach fits our reality?”

Her phone buzzed with another text from Miguel: “Tom wants to know if you can make his game Saturday. I told him you promised.”

Sarah looked at the message, then at the conference room where her team was finally starting to understand what they actually needed. The chaos of the morning had given way to clarity of purpose.

“Promised and will be there,” she typed back. “Some things are starting to make sense.” And for the first time since they’d begun this software selection journey, she actually believed it.