Sarah, still a bit noodling on the production visibility issues, arrived at Emma’s corner office to find Klaus already there, his face bearing the expression of someone who’d just received uncomfortable news. Patrick Chen, Alpine’s IT manager, sat across from him with his laptop open, the glow of spreadsheets reflected in his glasses. Emma stood by the window overlooking the shop floor, her back to them, shoulders rigid with the kind of tension that came from staring at numbers that didn’t make sense.

“Come in, Sarah,” Emma said without turning around. “Close the door behind you.”

The big conference table was scattered with printouts—Business Central reports, financial statements, and what looked like competitive analysis documents. Sarah recognized the format: the kind of emergency documentation that appeared when successful companies suddenly found themselves asking uncomfortable questions about their future.

“We have been walking through our quarterly numbers,” Emma said, finally turning to face them. “Klaus, you want to share what you told me about our operational costs?”

The Cost Crisis Revealed

Klaus shifted uncomfortably in his chair. “Overtime expenses are up fifty percent over last quarter. We’ve been running emergency weekend shifts almost every week. Temporary worker costs have tripled because we keep needing a lot of extra hands to meet deadlines.” He gestured at one of the printouts. “And we’re paying penalty fees for late deliveries that are eating into our margins.”

“How much in penalty fees?” Sarah asked, though she wasn’t sure she wanted to know the answer.

“Last quarter, we had six orders that were so late that the maximum penalties were due. This, combined with the deliveries that were only slightly delayed, added up to well over 100,000 Euros”, Patrick said, reading from his screen. “Which is more than we paid in the previous two quarters combined.”

Emma sat down heavily at the head of the table. “But that’s not the worst part. Patrick, show them the inventory analysis.”

Patrick pulled up another spreadsheet. “We’ve been building an inventory of standard components while simultaneously running out of custom parts needed for urgent orders. Our total inventory value is up 22%, but our inventory turnover is down 15%. We’re basically storing more money on shelves while having less of what we actually need for production. In addition, there is another negative inventory effect. Due to the sharp increase in lead times, the proportion of work in progress in the P&L, including our customer-specific orders, is rising. Since the valuation is based on production costs and not on sales, we are missing a considerable portion of our planned sales.”

The Uncomfortable Truth

Sarah felt the familiar knot in her stomach tighten. Every number Patrick was reading represented a symptom she’d witnessed firsthand on the shop floor. The overtime costs resulted from a lack of visibility and the resulting, desperate, last-minute schedule changes to address the constant pressure from delays. She also physically witnessed the inventory problems: On the one hand, there was the requirement to produce standard parts when work areas were at risk of running idle. On the other hand, there was a certain inability to master the dynamics of their make-to-order business in time.

As a result, she had seen work areas running idle while critical parts sat in the wrong locations or weren’t manufactured yet. The fact that lead times had increased dramatically over the years due to the business’s growing complexity was by no means new to her. However, she wasn’t aware that this had such significant implications for the P&L.

“Emma,” she said carefully, “what exactly are we looking at in terms of overall performance?”

Emma picked up a single sheet of paper—Alpine’s profit and loss statement for the quarter. She stared at it for a moment before speaking. “We’re looking at our first negative EBITDA since I founded this company in 1987.”

The room went silent except for the distant hum of machinery filtering through the windows. Sarah had known the numbers were bad, but seeing the impact on Emma—the woman who’d built Alpine from a small machine shop into a seventy-five million Euro business—made it real in a way that spreadsheets couldn’t.

“How negative?” Klaus asked quietly.

“Negative enough that if this trend continues for another quarter, we’ll be having a very different conversation about our future,” Emma replied.

The Paradox of Production

Patrick cleared his throat. “I’ve been trying to understand where the problems are coming from. Our ERP system shows that we’re actually producing more units than last quarter. Our quality metrics are strong. Customer satisfaction surveys are positive. But our costs are spiraling, and our delivery performance is getting worse. If you ask me, I don’t get this: we are producing more, but at the same time our revenue is way below plan. I am the IT guy. But to me, it feels that our units produced do not contribute to the throughput that we need to ship sales orders.”

“That’s what I don’t understand,” Klaus said, leaning forward. “We’ve got better equipment than we’ve ever had. We’ve got skilled workers. We’ve got more orders than we can handle. How are we losing money?”

Sarah looked around the table at her colleagues, each an accomplished professional who’d helped build Alpine’s success. Klaus with his deep understanding of customer needs and manufacturing processes. Patrick with his technical expertise and system knowledge. Emma with her decades of business wisdom. All of them staring at reports that described a company they barely recognized.

“I think,” Sarah said slowly, “the problem isn’t what we’re doing. It’s how we’re doing it.”

“What do you mean?” Emma asked.

Sarah thought about her morning on the shop floor, about Jenny spending two hours tracking down missing parts, about workers standing idle while materials sat in parking lots. “I mean, we’re trying to run a hundred-person manufacturing operation with the same systems and processes we used when we had thirty people. The scale has changed, but our approach hasn’t.”

The Production Visibility Issue

“Business Central handles the increased scale just fine,” Patrick said, a defensive edge creeping into his voice. “We can process more orders, track more inventory, and generate more detailed reports than ever before.”

“Taking about your reports”, Klaus said, trying to cool Patrick down a bit, “I noticed something strange. Yes, we process way more orders than we did a few years ago, when we were way smaller. Nevertheless, our revenue does not increase at the same rate as we seem to have a bigger average throughput time per order. In other words: our order completion curve is degressive, while our cost curve is progressive.”

Patrick looked at Klaus as if we would have said that a cigar-smoking zebra with a clown’s hat could solve all their issues.

“Let me try to say this differently”, Sarah said gently. “This morning, I watched our people spend hours searching for parts that your system said were in production. I watched workers wait for information that should have been readily available. I watched supervisors make scheduling decisions based on assumptions because they didn’t have real-time visibility into what was actually happening.”

Klaus frowned. “Are you saying the ERP system is the problem?”

“No, I’m saying the ERP system solves one set of problems really well—managing transactions, tracking finances, processing orders. But production isn’t just transactions. It’s physical parts moving through physical processes on finite capacities with real people making real-time decisions. And somewhere between our computer systems and our shop floor, we’ve lost visibility into what’s actually happening.”

The Two-Hour Search Example

Emma leaned back in her chair. “Give me a concrete example.”

Sarah pulled out her phone and checked her notes from the morning. “This morning, Jenny spent two hours trying to locate the Hoffmann precision couplings. According to Business Central, they should have been in final assembly. But they’d been moved three times, mislabeled, and confused with parts from a different order. Meanwhile, Schmidt finished an operation on the Brenner housings but didn’t know where to send them next because the routing information wasn’t available where he needed it.”

“But the routing information is in the system,” Patrick protested. “He could have looked it up.”

“On which computer?” Sarah asked. “The one that’s fifty meters away from his workstation and being used by someone else? Patrick, our shop floor workers don’t have tablets yet. They don’t have real-time access to system information. They’re making decisions based on paper routing sheets that get coffee spilled on them and verbal instructions that get lost in translation.”

The Informal Coordination Problem

The room fell quiet again. Through the window, Sarah could see Otto walking across the shop floor, stopping to talk with an operator at one of the CNC machines. Even from this distance, she could see the animated gestures of someone explaining a problem, the nodding of someone who understood, the collaborative problem-solving that happened when people who knew the work worked together to solve immediate challenges.

“There’s something else,” she said. “Otto told me this morning that our scheduling approach worked fine when we were smaller because everyone could see everything. Now we’ve got five times the people and ten times the complexity, but we’re still trying to coordinate everything through methods that assume everyone knows what everyone else is doing.”

“What are you suggesting?” Emma asked.

Sarah looked at the financial reports scattered across the table, then out at the shop floor below. “I’m suggesting that our operational problems and our financial problems are the same problem. We’ve grown past the point where informal coordination works, but we haven’t developed the systems and processes needed for formal coordination.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning Otto can’t walk the floor and know the status of every job anymore because there are too many jobs and too many variables. Meaning I can’t manage the schedule with a whiteboard because there are too many interdependencies and too many moving parts. Meaning our supervisors can’t coordinate activities effectively because they don’t have visibility into resource conflicts and material availability.”

Klaus rubbed his temples. “So, what’s the solution?”

Otto Enters the Conversation

Before Sarah could answer, there was a knock on the conference room door. Emma’s assistant peered in apologetically.

“I’m sorry to interrupt, but Otto Müller is asking if he can speak with you. He says it’s about the production schedule, and it’s important.”

Emma glanced around the table. “Send him in.”

Otto entered the room with the deliberate pace of someone who’d been thinking carefully about what he wanted to say. He nodded to everyone, then addressed Emma directly.

“I heard you were having a meeting about our operational challenges,” he said. “I thought you might want to hear from someone who’s been watching this problem develop for the past few years.”

“Please, sit down,” Emma said, gesturing to an empty chair. “What’s your perspective on what’s happening?”

Otto’s Historical Perspective

Otto settled into the chair with the careful movements of someone who’d spent decades on his feet. “When I started here twenty-eight years ago, we had eight people and maybe a dozen active orders at any time. I could tell you the status of every job just by walking around. Sarah’s whiteboard would have been overkill back then.”

He paused, looking around the table. “But somewhere in the last five years, that stopped working. Not because people got lazy or because the work got harder. Because the complexity grew faster than our ability to see it.”

“What do you mean by ‘see it’?” Patrick asked.

“I mean knowing what’s happening when it’s happening,” Otto replied. “This morning, I had three different people ask me where specific materials were. Not because they were lazy, but because there’s no easy way for them to find out. I had two supervisors trying to coordinate the same machine without knowing the other one was doing it. I had an operator finish a job and then wait twenty minutes for someone to tell him what to do next.”

Otto leaned forward. “The thing is, all the information they needed existed somewhere. In Sarah’s schedule, in Patrick’s computer system, in Klaus’s production plans. But it wasn’t where they needed it when they needed it.”

Production Visibility vs. Communication

“Are you saying we need better communication?” Klaus asked.

Otto shook his head. “I’m saying we need better visibility. Communication is talking to each other. Visibility is being able to see what’s happening without having to ask.”

Sarah found herself nodding. “That’s exactly what I was trying to explain. We can track our finances in real-time, but we can’t track our production in real-time.”

“And that,” Otto said, “is why we’re working harder but not smarter. Why we’re paying for overtime, and temporary workers, and penalty fees. Because we’re constantly reacting to problems instead of proactively managing them.”

Emma looked around the table. “So if visibility is the problem, what’s the solution?”

Otto was quiet for a moment, then smiled slightly. “That’s not really my area of expertise. I can tell you what’s wrong, but figuring out how to fix it? That’s going to require people who understand both the shop floor and the computer systems.”

He stood up. “But I can tell you this: whatever solution you come up with, it better works for the people who actually have to use it. Because the fanciest system in the world won’t help if the folks on the floor can’t or won’t use it.”

The Challenge Ahead

After Otto left, the room was quiet for several minutes. Finally, Emma spoke.

“Sarah, I want you to think about what Otto just said. About visibility and real-time information. Because if he’s right—if our operational problems are really visibility problems—then we need to figure out how to make our production as transparent as our accounting.”

“That’s going to require more than just tweaking our current systems,” Patrick said thoughtfully. “That’s going to require fundamentally rethinking how we connect the shop floor to our information systems. And we need to evaluate if and how our beloved whiteboard is impacted by this process.”

Klaus looked at the financial reports again. “How long do we have to figure this out?”

Emma’s expression was grim. “If these trends continue? Not long. We can’t afford another quarter like this one.”

Sarah felt the weight of that statement settle over the room. They weren’t just talking about improving efficiency or reducing costs. They were talking about the survival of a company that had been part of the community for nearly four decades.

Defining the Path Forward

“I think,” she said quietly, “we need to have a serious conversation about production scheduling. About how we plan work, how we coordinate activities, and how we make information available where and when it’s needed.”

“What kind of conversation?” Emma asked.

Sarah looked out at the shop floor, where she could see workers moving purposefully between machines, supervisors consulting clipboards, and the organized complexity of precision manufacturing continuing despite all the challenges they’d discussed.

“The kind where we admit that what got us here won’t get us where we need to go,” she said. “The kind where we figure out what comes after the whiteboard. To that extent, I already agree with what Patrick said a minute ago. The whiteboard is so cool. It is flexible, and I could and can fully tweak it to be ‘mine’. But it’s an isolated island. It is not connected with our beautiful new ERP. And if I didn’t talk to Otto all day long, it also would be disconnected from the shopfloor. And from that isolated island, we are supposed to schedule, manage, and run our daily core business—which is the manufacturing.”

Emma nodded slowly. “Alright. Sarah, I want you to take the lead on this. Work with Klaus and Patrick to figure out what our options are. But first—” she glanced at the clock on the wall “—don’t you have somewhere you need to be?”

Sarah’s eyes followed Emma’s glance, and her heart lurched. 17:35. Tom’s game had started thirty-five minutes ago. In her focus on Alpine’s crisis, she’d completely lost track of time.

“I have to go,” she said, already gathering her things. “But we need to continue this tomorrow morning. This conversation isn’t over.”

“Go,” Emma said firmly. “Some things are more important than quarterly reports. Even negative ones.”

The Rush to Tom’s Game

Sarah rushed out of the conference room, her mind still spinning from the meeting. First negative EBITDA since 1987. The weight of that number sat heavily in her chest as she hurried through the parking lot. Emma had built this company from nothing, had weathered recessions, and market downturns, and competitive pressures for nearly four decades. And now, on Sarah’s watch as production scheduler, they were losing money for the first time in the company’s history.

She fumbled with her car keys, her hands shaking slightly. Was it her fault? Had her inability to manage the increasingly complex schedule contributed to this crisis? The overtime costs, the penalty fees, the inventory problems—how much of that came down to the fundamental inadequacy of her whiteboard-based approach?

Her phone buzzed as she started the engine. A text from Miguel: “First half almost over. Tom scored! Hurry!”

Tom had scored. Her son had scored his first goal of the season, and she’d missed it. She’d been sitting in a conference room talking about negative EBITDA while her ten-year-old was experiencing one of the biggest moments of his young football career.

A Speeding Ticket

Sarah pulled out of the parking lot faster than she should have, her foot heavy on the accelerator as she navigated the industrial district toward the sports complex. The meeting replayed in her mind—Otto’s insights about visibility, Patrick’s defensive responses about the ERP system, and Klaus’s frustration with operational costs. They were all symptoms of the same fundamental problem: they’d grown beyond their ability to see and coordinate what was actually happening.

The irony wasn’t lost on her. She was rushing to see her son play football—something immediate, visible, happening in real-time—while Alpine struggled with the invisibility of its own production processes. At the football field, everyone could see exactly what was happening. The score was obvious. Player positions were clear. The next play was visible to coaches, players, and parents alike.

Her speedometer read 85 km/h in a 70 km/h zone. She eased off the accelerator, but only slightly. Tom had scored. Her son had scored, and she hadn’t been there to see it.

Blue lights flashed in her rearview mirror.

“Verdammt,” she muttered, pulling over to the shoulder. The police officer was polite but efficient—license, registration, explanation for her speed. Sarah found herself explaining about her son’s football game, about missing his goal, about trying to get there for the second half. The officer, perhaps a parent himself, was sympathetic but still wrote the ticket.

“Sixty euros,” he said, handing her the citation. “And drive safely. Your son needs his mother in one piece.”

Sixty euros. Another small cost added to a day full of costs—overtime, penalties, temporary workers, and now a speeding ticket earned while rushing between the crisis at work and the promises at home.

Arriving at the Game

She arrived at the sports complex with twenty-five minutes left in the game, parking hastily and jogging toward the field where she could hear the distinctive sounds of youth football—coaches calling out instructions, parents cheering, the thud of ball against foot. She spotted Miguel immediately, standing along the sideline with his distinctive blue baseball cap, and hurried over to him.

“How’s he doing?” she whispered, slipping her hand into his.

“Incredible,” Miguel said, beaming. “Goal in the twenty-third minute, beautiful shot from outside the penalty box. The coach moved him to center midfield, and he’s been everywhere.”

Sarah scanned the field and found Tom, his number 7 jersey bright against the green grass, his face flushed with exertion and concentration. He was exactly where Miguel said—everywhere. Reading the game, calling for passes, supporting his teammates.

“Has he seen me?” she asked.

“Not yet. He’s been completely focused.”

Tom’s Winning Play

The game flowed back and forth, both teams creating chances but unable to convert. With five minutes left, the score remained 1-1. Tom’s team pressed forward, looking for the winning goal. Sarah found herself caught up in the rhythm of the match, the immediate clarity of cause and effect that made football so different from the complex invisibility of manufacturing schedules.

With two minutes remaining, Tom received a pass at the top of the penalty box. Sarah held her breath as he turned, surveyed his options, and spotted a teammate making a run. Instead of shooting, he played an unselfish pass that created a better opportunity. The teammate scored, and Tom raised his arms in celebration—not for his own glory, but for his team’s success.

“That’s my boy,” Miguel said quietly, squeezing Sarah’s hand.

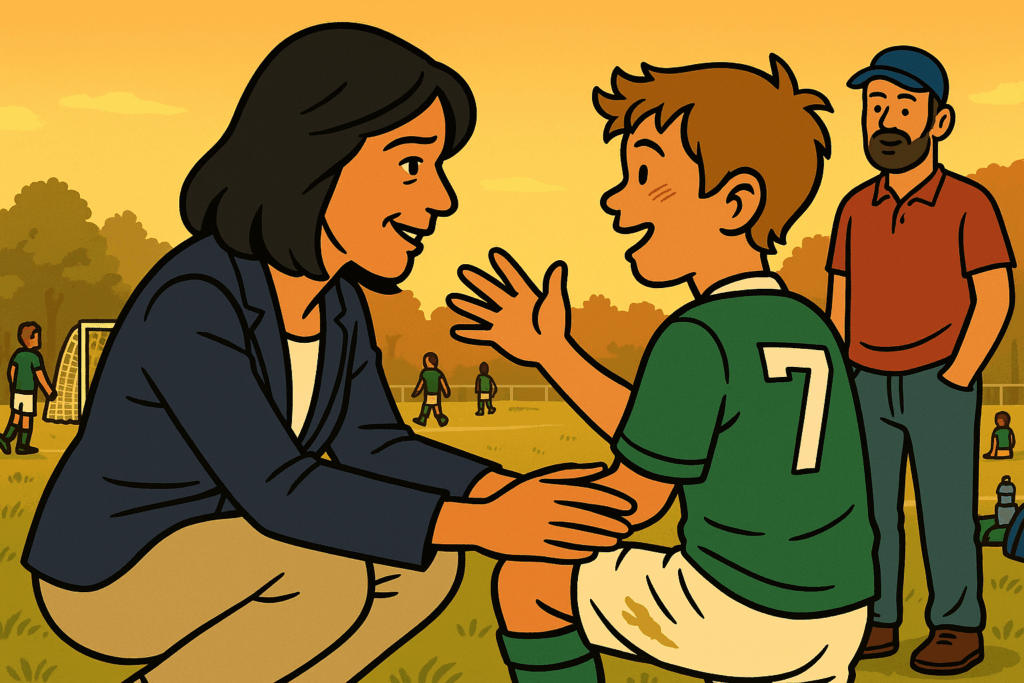

As the final whistle blew, Tom looked toward the sideline and spotted his parents. His face lit up with pure joy, and he jogged over, still breathing hard from the match.

“Mom! Did you see my goal?”

Sarah’s heart clenched. “I’m so sorry, sweetheart. I got here for the second half and saw you set up the winning goal. That was brilliant passing.”

Tom’s smile didn’t fade. “Dad recorded my goal on his phone. We can watch it together at home. And did you see how I read that defender’s movement? I knew exactly when to release the pass.”

The Revelation

Sarah knelt to Tom’s level, struck by his words. He’d read the defender’s movement. He’d seen what was happening and made the right decision at the right time. In football, unlike in manufacturing, you could see everything you needed to see to make good decisions.

“You played beautifully,” she said, hugging him tight. “I’m so proud of you.”

As they walked toward the car, Tom chattering excitedly about the match, Sarah’s phone buzzed with a text from Emma: “Have a good evening with your family. Tomorrow, we’ll figure out how to save the company.”

Sarah looked at her son, still glowing from his team’s victory, then at Miguel, who’d been there for every minute of Tom’s triumph while she dealt with Alpine’s crisis. Tomorrow, they would indeed figure out how to save the company. But tonight, she was exactly where she needed to be—with the people who mattered most, celebrating a victory that was visible, immediate, and real.

The question that would keep her up tonight wasn’t just what came after the whiteboard. It was about building a system that gave them the same kind of clarity on the shop floor that Tom had just demonstrated on the football field. The ability to see what was happening, understand the situation, and make the right decision at the right time. If a ten-year-old could read a game that clearly, surely they could find a way to make Alpine’s production just as visible.