A few days after the data quality revelations, the management team gathered for what Emma had announced as a “technical deep-dive” on setup optimization. Patrick had prepared a presentation analyzing their current setup practices, and the conference room buzzed with the anticipation of finally tackling a concrete issue with clear metrics.

“Let me start with some numbers,” Patrick said, projecting a chart showing machine utilization data for their CNC precision machining operations. “We’re spending approximately 30% of our total time on setups in precision machining. That’s the proportion of setup time versus total reported time at this stage.”

He clicked to another slide. “But here’s where it gets interesting. When we look at individual production orders, setups account for only about 10% of the total production order’s runtime. The discrepancy exists because we’re measuring different things—stage-level versus order-level metrics.”

Klaus leaned forward, studying the numbers. “So we have a significant setup component, but it’s spread across multiple machines and production orders. What’s the benchmark for job shops like ours?”

“Industry benchmarks suggest 15-20% setup time as a proportion of total stage time,” Patrick replied. “So we’re above that, but not dramatically.”

Sarah had been studying the data over the weekend. “Patrick, what’s the overall utilization rate for precision machining? Are we running at capacity?”

Patrick clicked on a capacity analysis. “Current utilization is around 75-80%. We have six CNC machines available at this stage, and we’re not running them at full capacity. Precision machining is definitely not our bottleneck right now.”

“Not a bottleneck?” Klaus said, his voice carrying a note of surprise. “Then why are we always scrambling with CNC work?”

“Because our scheduling is reactive,” Sarah explained. “We scramble because we don’t have good visibility, not because we lack capacity.”

The Philosophical Divide

Klaus pulled up a spreadsheet he’d prepared on his own. “Regardless of whether it’s a bottleneck, we’re clearly inefficient with setups. Look at this analysis—if we could reduce our setup time from 30% to 15% through better batching, sequencing, and running campaigns, we’d free up significant capacity for revenue-generating work.”

“Or,” Otto said from his corner seat, his voice carrying that particular tone that meant he was about to challenge something, “we could stop obsessing over internal efficiency metrics that our customers never ask about.”

The room went quiet. Klaus turned to face Otto directly.

“What do you mean by that?” Klaus asked, trying to keep his tone neutral.

Otto stood up and walked to the front of the room. “I mean that in my thirty years here, not once has a customer called to ask about our machine utilization rates. Not once has anyone asked whether we’re running setups efficiently. You know what they ask about?”

“Delivery dates,” Sarah said quietly.

“Exactly,” Otto confirmed. “They ask when they’re going to get their parts. And when we start batching jobs together to optimize setups, we’re telling some customers that their orders have to wait because we decided it’s more efficient to run less time-critical work first.”

Klaus’s face reddened. “Otto, I respect your experience, but we can’t ignore efficiency forever. Our margins are already thin. If we can reduce costs through better setup management, that directly impacts our competitiveness.”

“Does it?” Otto challenged. “Or does it mean we save some setup time while making our delivery performance worse? Because I’ve seen this movie before, Klaus. We tried setup optimization a bit more than a decade ago with that expensive consultant from Munich. Remember what happened, Emma?”

Emma nodded slowly. “We achieved better efficiency numbers on paper, but customer complaints increased. After three months, we went back to our old approach.”

Klaus looked surprised. “I didn’t know about that. But surely with modern scheduling software—”

“Software doesn’t change the fundamental trade-off,” Otto interrupted. “When you batch jobs for efficiency, some customers wait longer. That’s physics, not a software problem.”

Sarah’s Dilemma

Sarah felt the tension between the two men she deeply respected escalating. She glanced at Emma, who was watching the exchange with interest but seemed willing to let it play out.

“Can I try to reframe this?” Sarah offered. “I think Klaus and Otto are both identifying real issues.”

Both men turned to look at her.

“Klaus is right that our setup approach is completely ad-hoc,” Sarah continued. “Schmidt finishes a job and sets up for whatever’s next without any systematic thinking about efficiency. That’s wasteful.”

Klaus nodded with satisfaction.

“But Otto is right that our competitive advantage isn’t being the cheapest supplier—it’s being reliable and responsive,” Sarah added. “If we optimize for internal efficiency at the expense of delivery performance, we might save costs but lose customers.”

“So what’s your recommendation?” Emma asked.

Sarah hesitated. “I honestly don’t know. Our current approach provides neither efficiency nor reliability—it’s just random. But I’m worried that aggressive setup optimization could make things worse rather than better.”

Machine Efficiency vs. Order Throughput – Demystified

Henning, who had been listening quietly via video call, finally spoke up. “I’ve seen this debate in dozens of high-mix low-volume manufacturers. Setup optimization is one of the most misunderstood topics in manufacturing. Companies often pursue it without understanding whether it actually improves their bottom line. And I want to share a framework that might help you think about this differently.”

Everyone turned toward the screen.

“First, let’s talk about the difference between throughput and efficiency,” Henning began. “Efficiency measures how well you use your resources—machine utilization, setup time, labor productivity. Throughput measures how much revenue you generate by delivering products to customers.”

He pulled up a simple diagram. “In high-mix low-volume environments, optimizing for efficiency often destroys throughput. Normally, you cannot optimize both at the same time. So, we need to figure out which effect has the greatest impact on your EBIT in your specific case: efficiency measures or throughput-increasing measures. And we need to accept that there is no guarantee in the world that greater efficiency automatically translates into higher EBIT. The same is true regarding throughput.”

“Does that mean that we should forget about looking at being efficient on the shop floor?” Klaus stared at the screen showing Henning’s face. “This, Mr. Consultant, is more irritating than if you had told me that next year’s Bundesliga champion won’t be FC Bayern München, but 1860 München instead.”

“I’m not suggesting you ignore efficiency,” Henning replied. “I’m suggesting you think about efficiency differently. Let me ask you some specific questions about your precision machining operation.”

The Alpine Reality Check

Henning pulled up Patrick’s earlier analysis. “Patrick showed us that precision machining has six CNC machines, utilization around 75-80%, and it’s not currently a bottleneck. Setup time is 30% of total stage time, but only 10% per individual production order. Given these circumstances, let’s think about what costs you’re actually trying to optimize.”

He paused for effect. “In bottleneck operations, avoidable setup time costs you throughput—every minute spent on setups is a minute you can’t produce revenue-generating output. But in non-bottleneck operations like your precision machining, what costs do setups actually create?”

The room was quiet. Everyone looked at each other, realizing they’d been debating setup optimization without clearly understanding what costs they were trying to reduce.

“Otto,” Henning prompted, “you’re on the shop floor every day. What costs do you actually incur during CNC setups?”

Otto thought carefully. “Well, there’s the time the operator spends on the setup, but we’re paying him whether he’s setting up or running parts. There’s … cleaning and lubricating the fixtures and tooling. We use specific cleaning solutions and lubricants for different materials.”

“What else?” Henning asked.

“Increased scrap rate,” Otto said, warming to the analysis. “The first few parts after a setup are more likely to be out of spec while the operator fine-tunes everything. We usually run a few test pieces that don’t go to customers.”

“Anything else?”

Otto shook his head slowly. “Not really. The machines are already here, paid for. The operators are on a salary. The main variable costs are cleaning materials and the higher scrap rate during setup verification.”

Silence fell over the room as the implications sank in.

“So let me make sure I understand,” Klaus said slowly. “We’ve been debating how to optimize setups in an operation that isn’t a bottleneck, where the actual variable costs of setups are cleaning supplies and test pieces?”

“That’s exactly right,” Henning confirmed. “Don’t get me wrong—those costs are real. But are they your first priority in addressing a negative EBIT? Are they more important than improving delivery reliability to protect and grow revenue?”

Sarah felt something click into place. “We’ve been focusing on a problem that sounds important—30% setup time—without understanding whether it’s actually material to our business performance.”

The Data Reality

Patrick had been taking notes throughout the discussion. Now he spoke up. “There’s another issue here. Even if we decided setup optimization was a priority, we don’t have the data to do it effectively.”

He pulled up examples from Business Central. “Look at our setup time estimates. We have a standard setup time of 35 minutes for switching between bearing housing variants. But Otto, what’s the actual range?”

“Depends entirely on what you’re switching from and to,” Otto replied. “Going from one bearing housing size to a similar size? Maybe 20 minutes. Switching from bearing housings to agricultural components with completely different fixturing? Could be 90 minutes.”

“So our 35-minute estimate is meaningless,” Patrick said. “And we don’t have documented data on setup times for different item transitions. We’d need to create setup matrices showing the time required to change from each item type to every other item type.”

“How many combinations would that be?” Klaus asked.

“Hundreds,” Patrick replied. “If we keep it simple. Every possible item transition would need to be documented with accurate time estimates. And we’d need to keep that data current as we add new products or change processes.”

Sarah added, “This connects back to last week’s data quality discussion. We don’t have reliable routing times. We don’t have accurate setup estimates. How can we optimize something we can’t even measure accurately?”

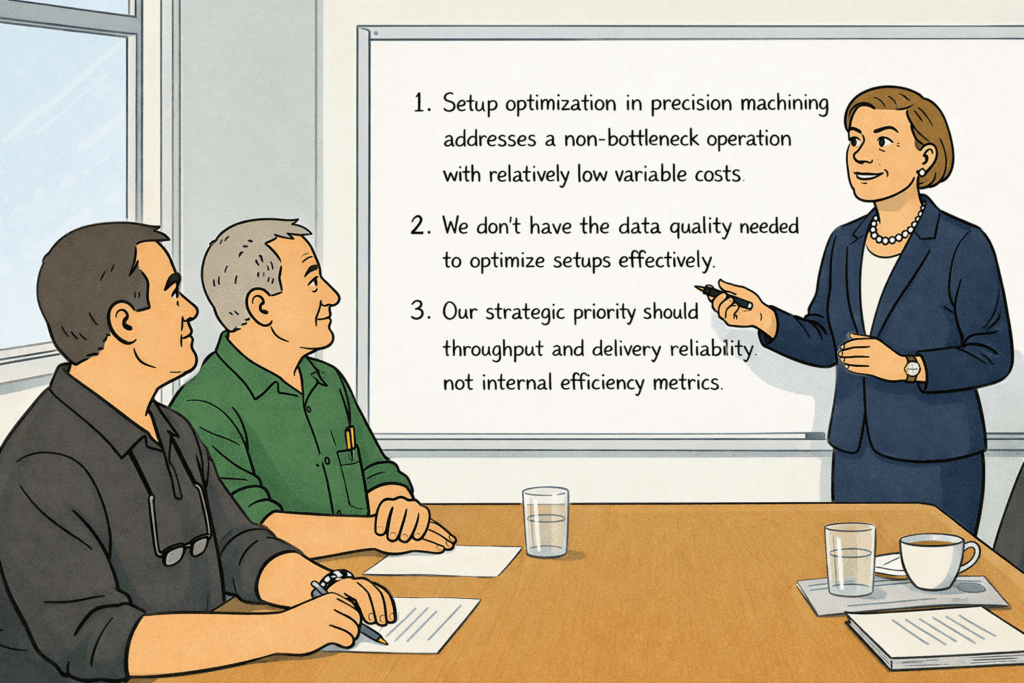

Emma had been listening carefully to the entire discussion. Now she stood and walked to the whiteboard.

“Let me summarize what I’m hearing,” she said, writing as she spoke. “One: Setup optimization in precision machining addresses a non-bottleneck operation with relatively low variable costs. Two: We don’t have the data quality needed to optimize setups effectively. Three: Our strategic priority should be throughput and delivery reliability, not internal efficiency metrics.”

She turned to face the group. “Does anyone disagree with those three points?”

The room was quiet. Even Klaus shook his head. “When you put it that way, I can’t argue. I still think we need to improve our setup efficiency eventually, but you’re right that it’s not the first priority.”

“So what is the first priority?” Emma asked.

The Resolution

Henning spoke up from the video screen. “The first priority is building the foundation for good scheduling—accurate data, clear processes, and alignment on goals. Setup optimization can come later, once you have visibility and control over your basic operations.”

He paused, then added, “But there’s one thing you could do immediately that would help without requiring sophisticated optimization.”

“What’s that?” Sarah asked.

“Subgrouping,” Henning replied. “Instead of treating all six CNC machines as interchangeable resources, logically group them. Maybe two machines primarily handle bearing housings, two handle agricultural components, and two are flexible for other work and to take production orders for either bearing housings or agricultural components if you face a temporary bottleneck there. That way, you naturally reduce the complexity of job transitions without formal optimization.”

Otto smiled. “You mean like what we’ve been doing informally for the past ten years?”

Everyone turned to look at him.

“What do you mean?” Emma asked.

Otto shrugged. “I’ve been routing similar work to the same machines for years. Machines one and two usually run bearing-related work because Schmidt and Weber know those setups cold. Machines three and four tend to run agricultural components. Five and six are our ‘wild cards’ for specialty work or when we need flexibility.”

“Why didn’t you mention this before?” Klaus asked, somewhere between amused and exasperated.

“Because I didn’t think it was a big deal,” Otto replied. “It’s just common sense. You put similar work on the same machines when you can, and you mix it up when you need to. I didn’t realize you all were going to spend hours debating whether to do something we’re already doing.”

Sarah started laughing, and after a moment, Klaus joined in. The tension that had been building throughout the meeting dissolved.

“So we’ve been debating setup optimization for precision machining,” Sarah said between laughs, “which isn’t a bottleneck, has low variable costs, and where we’re already doing informal subgrouping. Meanwhile, we have actual problems like data quality and delivery reliability that need attention.”

“That about sums it up,” Emma said with a smile. “This is why I love this team. We can spend two hours having an intense philosophical debate, only to discover that Otto solved the problem years ago without telling anyone.”

The Path Forward

Emma looked around the table with the kind of clarity that came from cutting through complexity to reach truth. “Here’s what we’re going to do. Patrick and Sarah, I want you to document Otto’s informal subgrouping approach. Not to optimize it—just to make it explicit so everyone understands the logic.”

“I can do that,” Sarah said, already making notes.

“And I will make sure”, Patrick added, “that I will continuously work on reflecting this in our routings. Basically, if we know this is a bearing housing job, we can assume Otto will most likely run it on machine 1 or 2. If we get this reflected in our routings, the system will better reflect reality, which will help with scheduling later on. Talking about scheduling: We also should ask the vendors if their software supports having alternative machine and work centers in the routing.”

“Good points, Patric”, Emma confirmed. “Now to you, Klaus. I want you to focus your analytical skills on something more impactful than setup optimization. Work with Patrick to identify which data improvements would have the biggest impact on our scheduling accuracy and delivery reliability.”

Klaus nodded. “That makes more sense than what I was doing.”

“And Otto,” Emma continued, “I want you to keep doing exactly what you’ve been doing, but also help Sarah and Patrick understand your decision-making process. Your informal knowledge needs to become documented knowledge.”

“Can do,” Otto said. “Though I still think you’re all making this more complicated than it needs to be.”

“Probably,” Emma agreed. “But that’s how we learn. We debate the complex approaches until we understand why the simple approaches actually work better.”

Henning added from the video screen, “What you’ve just experienced is exactly why I emphasize understanding before optimization. If you’d implemented sophisticated setup optimization software without this discussion, you would have automated a solution to a problem that wasn’t your real constraint. You would have created complexity without creating value.”

“Instead,” Emma said, “we now understand that our priority is improving data quality and delivery reliability. Setup optimization can wait until we have those foundations in place.”

“And when we do eventually tackle setup optimization,” Klaus added, “we’ll do it with better data and clearer understanding of what we’re trying to achieve.”

The Afternoon Reflection

After the meeting, Sarah found Otto in the break room, looking quietly satisfied.

“You’ve been doing subgrouping for more than ten years?” Sarah asked. “And you never mentioned it?”

Otto smiled. “Sarah, I’m a shop floor supervisor, not a business consultant. I don’t use fancy terms like ‘subgrouping’ or ‘setup optimization.’ I just try to make the workflow as smooth as possible. When I see that Schmidt does good work on bearing housings and has the right tooling already mounted, I route bearing housing work to his machine. It’s not complicated.”

“But it’s exactly what the consultants recommend,” Sarah pointed out.

“Maybe that’s because it’s common sense,” Otto replied. “The complicated approaches usually aren’t better—they’re just more expensive to implement and harder to explain.”

Sarah thought about the morning’s debate—Klaus’s spreadsheets showing potential efficiency gains, Patrick’s analysis of setup percentages, Henning’s frameworks about throughput versus efficiency. And underneath all that complexity, Otto had been quietly solving the problem through practical judgment.

“Do you think scheduling software will help us,” Sarah asked, “or will it just complicate things that work fine already?”

“Good software will help,” Otto said. “But only if we use it to make our good practices more visible and consistent, not to replace judgment with algorithms. What I do informally needs to become systematic so it doesn’t depend on me being here. That’s where the software can help.”

He stood up to head back to the shop floor. “Just remember, Sarah—the goal isn’t to have the most sophisticated scheduling system. The goal is to ship orders on time so customers are happy and we can grow the business. Everything else is just details.”

Sarah watched him leave, thinking about how the morning’s intense philosophical debate had resolved into something simple: focus on throughput and delivery reliability, document what works, improve data quality, and don’t optimize what isn’t broken.

They still had a long way to go in selecting and implementing scheduling software. But at least now they knew what they were optimizing for—and just as importantly, what they weren’t.