Sarah Martinez arrived at Alpine Precision Components GmbH fifteen minutes early on Monday morning, coffee in hand and optimistic about tackling the week ahead. That optimism lasted exactly thirty-seven seconds—the time it took her to notice the voicemail light blinking urgently on her desk phone and to spot the hastily scrawled note Jenny had left on her keyboard: “Mazak #3 down. Heat treatment delayed. Müller material MIA. Call Otto ASAP!”

She stared at the note, her stomach sinking as the implications cascaded through her mind like dominoes falling in slow motion. The order for Brenner Industries—their biggest customer and the one Klaus had personally promised would ship by Wednesday—required parts from a specific CNC machine, called Mazak #3. The heat treatment batch for the agricultural equipment components was supposed to come back from the subcontractor today, but if it was delayed… She grabbed her phone and started dialing.

“Otto? It’s Sarah. What happened to our Mazak #3 baby?”

“Hydraulic pump gave up sometime after we left Friday,” came Otto’s gravelly voice through the speaker. “Werner tried to get it running this morning, but we need a new seal assembly. The earliest the supplier can get us the part is Wednesday afternoon.”

The Illusion of Control

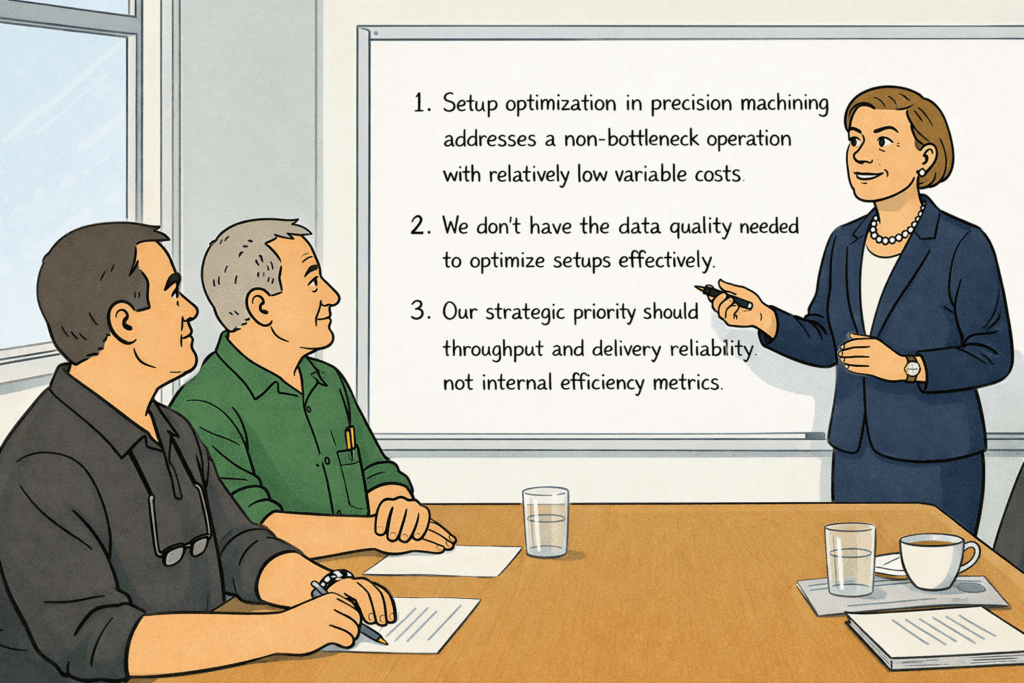

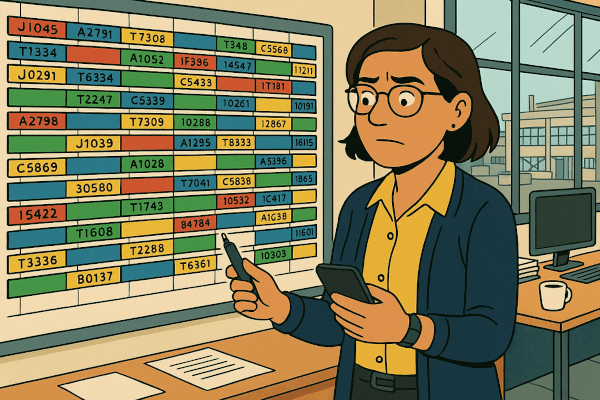

Sarah’s eyes moved to the color-coded production scheduling whiteboard that dominated the wall behind her desk—a maze of magnetic strips, colored markers, and hastily written job numbers intended to represent Alpine’s entire production schedule. Every job had multiple production steps. Hence, a sophisticated system of numbering and color coding represented both the production order and its operations. Each series of numbers and color-coded strips represented the different orders, arranged in neat rows by machine and time slot. It looked organized, systematic even. But looking at it now, with Mazak #3 suddenly unavailable for three days, she realized it was nothing more than an elaborate illusion of control.

“What about the Brenner job?” she asked, already knowing the answer would complicate everything else.

“That’s the problem,” Otto sighed. “Those bearing housings can only run on machine three or five. Five’s booked solid through Thursday with the Kemper series.”

Sarah grabbed a dry-erase marker and started moving magnetic strips around on the board, trying to visualize how she could shuffle the schedule. Move the Kemper job to machine four? No, machine four couldn’t handle the part geometry. Split the Brenner order between multiple machines? The setup would eat up more time than they’d save.

Her phone buzzed with a text from Miguel: “Tom’s game moved to 17:00 today. Can you make it?”

She stared at the message, then at the whiteboard, then back at the message. Her ten-year-old son’s football game versus the scheduling crisis that was about to consume her entire day. It shouldn’t even be a choice, but the gnawing anxiety in her stomach told her which one was going to win.

Klaus Wants Answers

The office door burst open, and Klaus Brenner strode in, his face already flushed with the kind of irritation that usually preceded uncomfortable conversations with customers.

“Tell me we can still make Wednesday for Brenner Industries,” he said without preamble.

Sarah looked at the whiteboard again, calculating rapidly. “If we can get machine three running by Wednesday afternoon and if the heat treatment comes back today instead of tomorrow and if—”

“Sarah.” Klaus’s tone was sharp. “I don’t need ifs. I need a delivery date I can stand behind.”

She felt heat rising on her cheeks. This was the awkward and stressful position she found herself in every Monday morning—and Tuesday morning, and Wednesday morning. Everyone needed definitive answers based on indefinite information. The whiteboard showed what should happen, but the gap between should and would was where her credibility went to die.

“The earliest I can promise with confidence is Friday,” she said finally.

Klaus ran his hand through his graying hair. “Brenner’s going to love that. This is the third time in two months we’ve moved their date.”

The Heat Treatment Disaster

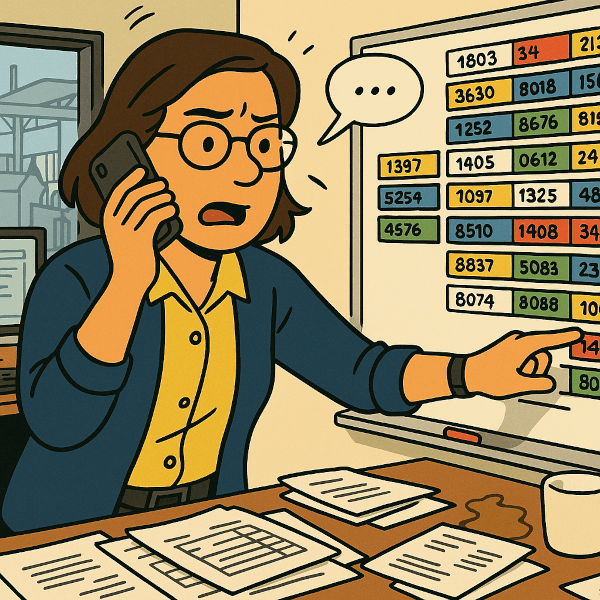

As if summoned by the mention of customer problems, Sarah’s desk phone rang. The caller ID showed Steinberg Surface Tech—the company whose heat treatment batch was apparently delayed.

“Sarah Martinez,” she answered, trying to keep her voice steady.

“Ms. Martinez, this is Hans from Steinberg. About your heat treatment batch that was supposed to be ready today…”

She closed her eyes. “Please tell me it’s just running a few hours behind.”

“I’m afraid not. We had a furnace malfunction over the weekend. Your parts are fine, but we need to recalibrate the entire system before we can release them. Wednesday morning at the earliest.”

Sarah made notes as Hans explained the technical details, but her mind was already racing through the implications. The agricultural components couldn’t ship until the heat-treated parts came back. That customer had a narrow delivery window for their planting season. If they missed it, the order might be cancelled entirely.

The Cascade Effect

After hanging up, she turned back to the whiteboard and started erasing and redrawing magnetic strips with increasing frustration. Every change created new conflicts. Moving one job affected the setup sequence on multiple machines. Moving one operation from one job on one machine always meant breaking things. It either affected the setup sequence. Or it pushed out other operations from other jobs—impacting their delivery time and cascading into further downstream headaches. The whiteboard that had seemed manageable on Friday afternoon now looked like a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces.

“Problems?” Otto appeared in the doorway, coffee mug in hand.

“The heat treatment delay just killed our Thursday delivery for Agrar-Tech,” Sarah said, gesturing at the board. “And I still haven’t figured out how to handle the Brenner situation.”

Otto’s Uncomfortable Truth

Otto studied the whiteboard with the calm attention of someone who’d been watching production schedules evolve for nearly three decades. “You know what the real problem is?” he said after a long moment.

“Mazak three?” Sarah suggested hopefully.

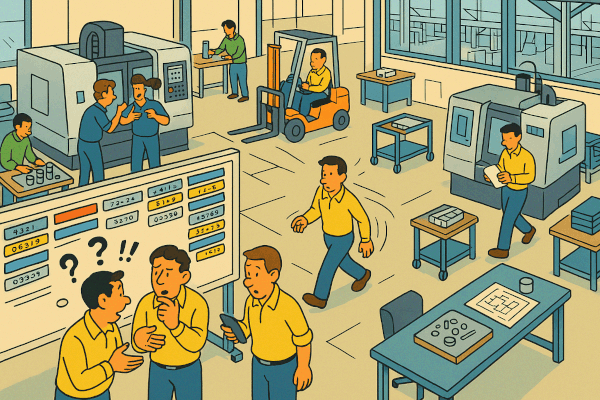

Otto shook his head. “The real problem is that this—” he gestured at the whiteboard “—shows us what we planned to do, but it doesn’t show us what we’re actually doing. Right now, I’ve got Müller and Schmidt standing around at Mazak four because they’re waiting for material that was supposed to arrive on Friday. I’ve got Weber trying to set up for the Steinbach job, but half the tooling is still mounted on machine six. And somewhere out there—” he waved vaguely toward the shop floor “—we’ve got parts for three different customers sitting in various stages of completion, but nobody knows exactly where they are or when they’ll be ready.”

Sarah slumped in her chair. She’d been so focused on moving magnetic strips around that she’d forgotten about the material shortage for another job entirely. “The Steinbach material—was that the delivery that never showed up?”

“Supposed to be here Friday afternoon,” Otto confirmed. “Jenny called the supplier three times. They keep saying it’s ‘on the truck,’ but the truck driver seems to be taking the scenic route, making a stop in every beer garden in our beautiful Bavaria.”

Her phone buzzed again. Another text from Miguel: “Should I tell Tom you might miss the game?”

Sarah stared at the message, feeling the familiar weight of disappointment settling in her chest. She’d missed Tom’s last game because of a customer emergency. The one before that had been cancelled due to her weekend scheduling crisis. Her son was starting to expect her absence rather than her presence, and that hurt more than any production deadline.

The Production Scheduling System That Stopped Working

“I need to make some calls,” she told Otto, reaching for her phone to contact their material supplier.

“Sarah,” Otto said gently. “You know this isn’t working, right?”

She looked up from her phone. “What isn’t working? The production scheduling?”

He nodded toward the whiteboard. “This worked fine when we were a twenty-person shop with maybe thirty active orders at any given time. But look around.” He gestured toward the window overlooking the shop floor, where nearly a hundred employees were navigating between machines, workstations, and material carts. “We’ve got five times the people, ten times the complexity, and we’re still trying to run everything like it’s 1995.”

Sarah followed his gaze to the shop floor below. Even from her office window, she could see the signs of confusion he was talking about. Small clusters of workers gathered around machines, clearly discussing something. An operator walking from station to station, obviously looking for something. A forklift operator waiting while someone consulted a clipboard, trying to figure out where a pallet should go.

“The whiteboard tells us what machines to use when,” Otto continued. “But it doesn’t tell us where the materials are, or which operator should run which job, or what happens when—God forbid—we get one of those rush orders that Klaus loves so much.”

A Rush Order Gets In

As if the universe had a sense of timing, Sarah’s phone rang. The caller ID showed Alpine’s main number, which meant Jenny was transferring a call.

“Sarah, it’s a customer calling about a rush order,” came Jenny’s harried voice. “Something about needing custom shaft couplings for a production line that’s down in Stuttgart. They’re willing to pay premium pricing if we can turn it around in three days.”

Sarah looked at Klaus, who had perked up at the mention of premium pricing. She looked at Otto, who was shaking his head with the weary expression of someone who’d seen this movie too many times. She looked at the whiteboard, where every available slot was already filled with carefully planned work.

“Tell them I’ll call back in ten minutes,” she said to Jenny.

After the call ended, the three of them stood in silence for a moment, staring at the colorful chaos of the production schedule.

“You know what the worst part is?” Sarah said, finally. “I can move these magnets around all day long, but I still won’t know if we can actually deliver what I’m promising. The board shows me when jobs are supposed to start and finish, but it doesn’t show me the ten things that could go differently in between. It doesn’t show me that Weber needs a specific tool that might be in use somewhere else, or that the quality inspection for the Hoffmann job always takes twice as long as we estimate, or that our best CNC operator is taking a vacation next week. It is just too far away from our shopfloor reality.”

Klaus checked his watch. “I need to call Brenner Industries back with a delivery date. What am I supposed to tell them?”

Sarah looked at the whiteboard one more time, trying to calculate the probability that all the pieces would actually fall into place as planned. Machine repairs on schedule. Materials arriving when promised. No quality issues. No additional rush orders. No sick employees. No unexpected customer changes.

The probability, she realized, was essentially zero.

“Tell them Friday,” she said. “And hope we get lucky.”

An Email Adding More Urgency

As Klaus left her office, probably to make an uncomfortable phone call, Sarah’s computer chimed with an email notification. The subject line made her heart sink: “Urgent: Change Request for Order #7734.”

She didn’t even need to open it to know what it contained. A customer who needed to modify their order, or change the quantity, or adjust the specifications, or move up the delivery date. Any of which would require her to start this entire scheduling exercise over again.

Her phone buzzed. Miguel again: “Tom’s asking if you’ll be there. Should I tell him yes or maybe?”

What’s next?

Sarah stared at the text message, then at the whiteboard, then at her computer screen showing the unopened urgent email. Somewhere in the complexity of production schedules and customer demands and machine breakdowns, she’d lost sight of the simple truth that Otto had just voiced: this approach to scheduling wasn’t working anymore.

The problem wasn’t just that Mazak #3 had broken down, or that the heat treatment was delayed, or that materials hadn’t arrived on time. The problem was that their entire system for managing production was built on the assumption that everything would go according to plan. And in Alpine’s dynamic manufacturing environment with a hundred employees and hundreds of active orders, things never went according to plan.

She picked up her phone to reply to Miguel, then set it down again. Then picked it up again.

“Tell him maybe,” she typed, then immediately deleted it.

“Tell him I’ll try my best,” she wrote instead, knowing that her best might not be good enough, and that something fundamental needed to change before it ever would be.

Outside her office window, the shop floor hummed with activity that looked purposeful from a distance but was, she now realized, largely reactive chaos dressed up as organized work. Somewhere in that organized chaos were parts for customers who were counting on Alpine to deliver on time, employees who were doing their best with incomplete information, and a business that was growing faster than its systems could handle.

The whiteboard had served them well for many years, but Otto was right—it belonged to an earlier, simpler time. The question was: what came next?