Two weeks after Henning’s framework presentation, Sarah found herself watching the third software demonstration of the week. This time, the vendor—a well-established scheduling software company with an impressive client list—was showcasing their solution through a polished presentation.

“As you can see,” the sales consultant said, clicking through vibrant Gantt charts and capacity views, “our system provides complete visibility into your production schedule. Production orders flow seamlessly across work and machine centers, respecting all capacity constraints and delivery commitments.”

The demo looked spectacular. Colorful bars moved across the timeline with satisfying precision. Machine utilization graphs showed perfect balance. Delivery date promises aligned beautifully with capacity availability. Everything worked exactly as it should in a world where data matched reality.

Klaus leaned over to Sarah. “This looks really good. Much better than the whiteboard approach.”

Sarah nodded, though something nagged at her. The demo data seemed almost too perfect—every production order had precise runtime estimates, every machine had predictable capacity, and every material arrived exactly when expected.

“Can we see how it handles Alpine’s actual data?” Emma asked, echoing Sarah’s unspoken concern.

“Of course,” the consultant replied smoothly. “That’s exactly what we propose for the trial phase. We’ll import your Business Central data, and you’ll see your real production schedule optimized according to your actual constraints.”

By Friday afternoon, Alpine had narrowed its selection to three candidates, all offering free but guided trials. Emma approved Patrick’s plan to work with each vendor to import Alpine’s real data and test how the systems perform in their actual production environments.

“This is where theory meets reality,” Henning said as the team discussed the trial approach. “The demos all look great with clean demo data. Now we’ll see what happens when these systems encounter your real-world complexity.”

The First Cracks Appear

The following Monday, Patrick sat with the first vendor’s implementation consultant, a young technical specialist named Thomas, who exuded confidence about data integration.

“Business Central’s data export is straightforward,” Thomas explained. “We’ll pull your production orders, routings, BOMs, work and machine center calendars, and resource assignments. The connector handles all the technical details automatically.”

Patrick watched as Thomas ran the import routine. Data flowed from Business Central into the scheduling system with impressive efficiency. Within minutes, Thomas had loaded Alpine’s entire production dataset.

“Now let’s generate your optimized schedule,” Thomas said, clicking the scheduling engine.

The system churned for quite a while, then displayed the results. Thomas’s confident smile faltered almost immediately.

“That’s … interesting,” he said, scrolling through the schedule. “Your system shows machine three scheduled for 194 hours this week. That’s physically impossible unless you’re running 24/7 and your week has eight days and two extra hours.”

Patrick leaned in to look at the screen. “How is that happening?”

Thomas clicked through several views, his expression growing more concerned. “I don’t know. It seems like a master data quality issue. It looks like your shop calendar shows machine three available 24/7, and the system is taking that literally. Also, it seems that somehow you made a setting that ‘grants’ you some extra time on that machine. Let’s set this aside for a minute and focus on your actual machine hours. You don’t actually run machines around the clock, do you?”

“No,” Patrick said. “We run two shifts Monday through Friday, with occasional Saturday overtime.”

“Then your work center calendar isn’t accurate,” Thomas replied. “The scheduling system can only work with the data it receives. If the calendar says 24/7 availability, it schedules 24/7.”

Patrick made a note. They’d need to fix the shop calendars before any scheduling software would work correctly.

“What about these routing times?” Thomas continued, pointing to another anomaly. “Machine five shows a setup time of zero minutes for this bearing housing operation. That can’t be right.”

Patrick checked the Business Central routing. “It shows zero because we did a copy-paste from another routing and forgot to update the setup time. In reality, that setup takes about thirty minutes.”

“About thirty minutes?” Thomas asked. “Or exactly thirty minutes?”

“Well … it depends,” Patrick said. “If we’re coming from a similar job, maybe twenty minutes. If we’re switching from something completely different, maybe forty-five minutes.”

Thomas sat back in his chair. “That’s sequence-dependent setup time. The system can handle that, but you need to define setup matrices showing how long it takes to change from each job type to every other job type.”

Patrick felt a sinking sensation. “How many combinations are we talking about?”

“In your environment? Probably thousands. Every possible job transition would need a documented setup time.”

“That is exactly the reason why we don´t want to focus on that topic here and now. Especially as the setup times of our precision machines are not significantly crucial overall.”

Sarah’s Discovery

That afternoon, Sarah sat with Klaus reviewing the results from the second vendor’s trial import. This system had successfully loaded Alpine’s data and generated a schedule, but the results looked bizarre.

“Why is it scheduling the Hoffmann precision components before we even receive the raw materials?” Klaus asked, pointing at the screen.

Sarah checked the Business Central purchase order. “The material is due Friday, but the system has scheduled production to start Monday. How did it make that mistake?”

Klaus dug deeper into the settings. “Look at the item master data. The lead time is set to three days, but that’s from two years ago, when we had a different supplier. Our current supplier typically takes seven to ten days, depending on their schedule.”

“So Business Central has outdated lead times?” Sarah asked.

“Apparently. And the scheduling system trusted that data.” Klaus scrolled through more items. “Actually, looking at this, I’d bet half our lead times are wrong. We update them when we remember, but there’s no systematic process.”

Sarah opened her notebook and started a list: “Master Data Quality Issues to Fix.” Under it, she wrote:

- Shop calendar doesn’t reflect actual availability

- Setup times missing or incomplete

- Material lead times outdated

By the end of the afternoon, the master data quality issues list had grown to seventeen items.

The Subcontracting Revelation

Wednesday brought Patrick back together with Thomas to address the master data quality issues. They’d spent Tuesday updating Business Central’s shop calendars to reflect actual operating hours and had begun documenting standard setup times.

“Much better,” Thomas said as he reran the scheduling engine. “Now your capacity utilization looks realistic. But I’m seeing another issue—this agricultural component order shows operations at both your facility and an external heat treatment vendor.”

“That’s correct,” Patrick said. “We do the initial machining, send parts out for heat treatment, then do final operations here.”

“But your routing doesn’t show which operations are internal versus external,” Thomas pointed out. “The system is trying to schedule the heat treatment operation on your shop floor machines.”

Patrick pulled up the routing in Business Central. “The operations are numbered, and we know from experience that operation 30 is always external heat treatment. But you’re right—there’s nothing in the data that explicitly identifies it as outsourced.”

“How does your scheduling system currently handle this?” Thomas asked.

“Sarah knows which operations are outsourced,” Patrick said. “She schedules the internal operations and leaves gaps for the external work. Also, if we need heat treatment to be done, we just send a purchase order to our supplier.”

“So it’s tribal knowledge,” Thomas said. “The scheduling software can’t read Sarah’s mind. We need explicit data showing which operations are internal, which are external, and what the lead times are for external operations. I am sure that when you schedule subcontracting work, you implicitly think in days rather than in minutes as with your own machines.”

Patrick added to his growing list of master data quality issues: “18. External operations not identified in routing data.”

Routing Line Zero

“There is another thing that I noticed”, Sarah added. “When I look at the visual schedule, there are a lot of very thin vertical lines that I see on every machine. They make a lot of visual noise, if I may say so. What’s this?”

Thomas picked this up. “Good observation. I saw the same and agree. There is a lot of clutter. It comes from your routing definitions. It seems that you have quite a few routing lines with zero times: zero setup, zero runtime, zero wait time, zero transport time. If there is no time for an operation, the visual schedule has to show it as a thin vertical line. Why did you define your routings like this?”

Sarah looked at Patrick. Patrick looked at Klaus. And Klaus looked at both Sarah and Patrick. You could grasp the confusion.

Finally, Patrick nodded. “I think I remember what we did and why. We still print our routing sheets as production order travelers. When we hand out the papers to the shop floor, we want to give some instructions to the operators. If I recall right, we decided to use zero-time routing lines for these operations. So far, they have neither hurt us scheduling-wise nor cost-wise.”

“You are absolutely right”, confirmed Klaus. “We need these instructions. They actually make sure that the guys on the shop floor do the right things right. They are a must.”

“Well”, said Thomas. “If you want to benefit from good scheduling software, you need to rethink this. You could consider using Business Central’s comment fields instead – and find an elegant way of printing them with your travelers. This won’t be easy, but will fix some further data issues with your routings when it comes to scheduling.”

Patrick answered: “Already added 19 to our master data quality issues list. Review ‘routing lines zero’ and find alternative solution”.

The Uncomfortable Pattern

By Thursday afternoon, Emma called an emergency meeting. All three vendor trials had revealed similar problems—not with the software, but with Alpine’s master data quality.

“Let me make sure I understand,” Emma said, looking around the conference room. “None of these scheduling systems can work properly because our master data is inadequate?”

“That’s the uncomfortable truth,” Patrick admitted. “Business Central has been working fine for financial management and order processing because those functions are more forgiving of data quality issues in manufacturing. But scheduling requires precision. When the system says an operation takes fifteen minutes, it needs to really take fifteen minutes—not ‘about fifteen minutes, give or take half an hour.'”

Henning, who’d been observing the trials remotely, joined via video call. “This is exactly what I warned about during our initial conversations. Garbage in, garbage out. The most sophisticated scheduling algorithm in the world can’t overcome bad input data.”

“But our data isn’t ‘bad,'” Klaus protested. “It’s estimates. That’s how manufacturing works—you estimate times and adjust based on reality.”

“For financial planning, estimates are fine,” Henning replied. “But for operational scheduling, too vague estimates create chaos. If you tell the system an operation takes fifteen minutes but it actually takes forty-five, every downstream calculation is wrong. The schedule that looked perfect becomes impossibly optimistic.”

Sarah had been quiet, processing the implications. “How much of our master data is actually accurate?” she finally asked.

Patrick pulled up his analysis. “I’ve been tracking the issues we’ve found. Routing times are rough estimates that haven’t been validated in years. Shop calendars don’t reflect maintenance schedules or actual shift patterns. Material lead times are based on supplier promises or the purchase department’s best guesses, not historical performance. Setup times are missing, too.”

He paused. “If I had to estimate, maybe thirty percent of our manufacturing master data is accurate enough for operational scheduling. The other seventy percent works fine for what we’ve been using it for, but it’s not scheduling-grade.”

The Specific Examples

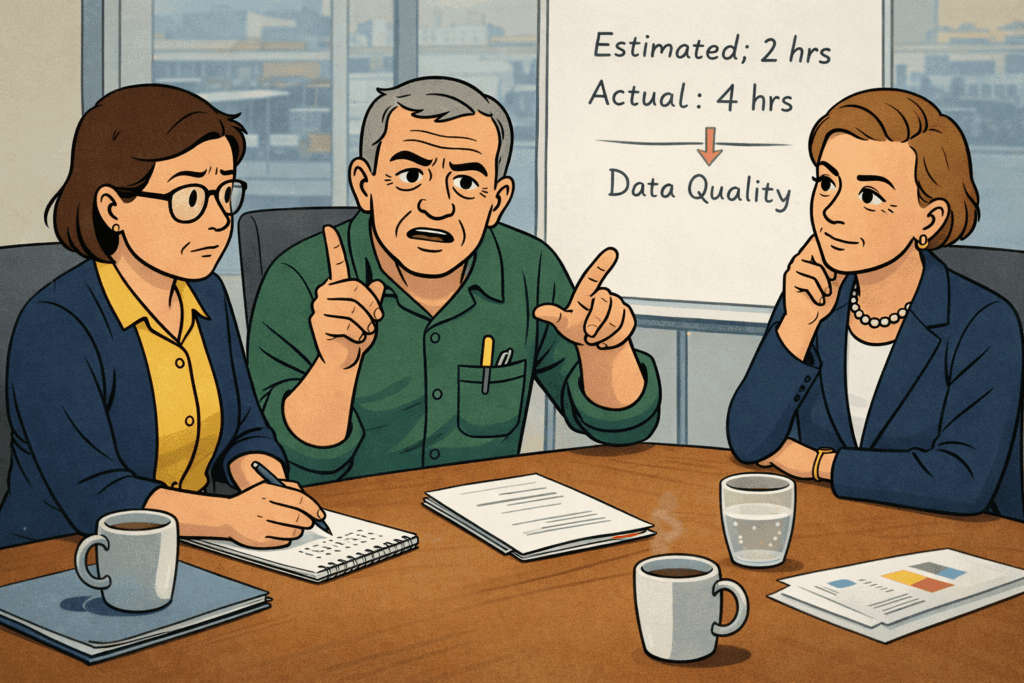

Otto spoke up from his corner seat. “Let me give you a real example. Last week, Sarah’s schedule said the bearing housing operation would take two hours. I assigned Hans Weber to run it, and it took four hours. Not because Hans is slow—he’s one of our best operators. But the job before it used completely different tooling, so setup took longer than planned. Then we discovered a quality issue from the previous operation that required extra inspection time. Then the coolant level was low, and we had to refill mid-job.”

He leaned forward. “Now, how do you put that into a computer system? The ‘estimated’ time was right for ideal conditions. But ideal conditions almost never happen.”

“That’s exactly the challenge,” Henning said through the video screen. “Scheduling systems need reliable data. But in a high-mix, low-volume environment like yours, variability is the norm, not the exception.”

Klaus looked frustrated. “So are you saying we can’t use scheduling software?”

“No,” Henning replied. “I’m saying you need to understand what data needs to be accurate versus what can remain approximate. And you need processes to keep critical data current.”

Sarah pulled out the documentation she’d created weeks ago—the twelve-page description of her actual scheduling process. “When I schedule manually, I adjust for all these variables mentally. I know machine three tends to run slower on Mondays after weekend downtime. I know Stefan is faster than Hans on precision boring operations. I know heat treatment always takes an extra day compared to what the supplier promises.”

She looked around the table. “All that knowledge is in my head, or Otto’s head, or Klaus’s experience. None of it is in Business Central.”

The Master Data Quality Discussion

Patrick projected a spreadsheet showing the routing for the bearing housing operation—the one that had caused problems in multiple vendor trials.

“This is what Business Central knows about this operation,” he explained. “Machine: Mazak #3. Setup time: 15 minutes. Runtime: 8 minutes per piece. That’s it.”

He clicked to another screen. “This is what actually affects how long this operation takes: Which job ran before it, and what tooling was mounted. Which operator is assigned and their experience level. Whether raw material is exactly to specification or slightly out of tolerance. The time of day—morning versus the end of shift affects quality and speed. Whether the machine was recently calibrated or is near the calibration due date.”

“How do we capture all that?” Klaus asked.

“You don’t,” Henning said. “At least not in master data. Some of it can be tracked—operator skill levels, machine calibration schedules. But some of it will always remain human judgment.”

“Then how do scheduling systems handle it?” Emma asked.

“Good systems help you make informed decisions quickly,” Henning replied. “They show you the schedule based on your data, highlight conflicts and constraints, and make it easy to adjust when reality differs from estimates. They don’t try to be smarter than your experienced schedulers—they make your schedulers more effective. However, those systems only benefit you if you accept the ultimate truth that there is no perfect schedule.

A schedule always projects the future, and nobody can predict the future precisely. Hence, the nature of a schedule is that there will be changes to it. You need to mentally accept this, define those areas that you need black and white versus those areas that can remain grey, and most importantly: you need to define processes and rules for how to deal with deviations.”

The Weekend Work

That evening, Sarah sat at her kitchen table reviewing the data quality issues they’d discovered. The list had grown to twenty-three specific problems, ranging from missing setup times to incorrect capacity calculations to outdated material specifications.

Tom was doing homework across from her, occasionally glancing up at his mother’s concerned expression.

“More work problems?” he asked.

“Data problems,” Sarah corrected. “We’re trying to use computer software to help schedule production, but the computer only knows what we tell it. And we haven’t been telling it very accurate information.”

“Like when I tell you dinner will take ‘a few minutes’ but it actually takes twenty minutes?” Tom asked with a slight grin.

Sarah laughed despite herself. “Exactly like that. Except when I schedule production based on estimates that are that far off, customers don’t get their orders on time.”

Miguel appeared from the kitchen with three cups of tea. “How bad is it?”

“Bad enough that we can’t really start using scheduling software until we fix our data,” Sarah said. “Which means more work before we can get the benefits we were hoping for.”

“How long will that take?” Miguel asked.

“Patrick thinks at least two weeks to get the critical data cleaned up,” Sarah replied. “And that’s just the essential routing times and calendar accuracy. Full data accuracy could take between one and two months.”

“Can you do it while still keeping production running?” Miguel asked.

That was the question that had been nagging at Sarah all week. “We’ll have to. We can’t stop production to clean up data. We need to improve the data while using it.”

Tom looked up from his homework. “That’s like trying to fix your bicycle while you’re riding it.”

“That’s exactly what it’s like,” Sarah agreed. “And it’s going to be messy.”

Monday’s Reality Check

Monday morning found the management team reconvened, this time with a more sober understanding of their situation. The vendor trials continued, but everyone now understood they were really conducting an audit of Alpine’s data quality rather than evaluating software capabilities.

Emma opened the meeting with characteristic directness. “We’ve learned three important lessons from these trials. First, scheduling software can’t overcome bad data. Second, we have more bad data than we thought. Third, fixing the data is going to take significant time and effort.”

She looked around the table. “The question is: do we fix the data first and then implement software? Or do we accept that our data will be imperfect and work with it?”

“False choice,” Henning said, joining again via video. “You need to do both. Select software that can work with imperfect data—systems that make it easy to override estimates and adjust for reality. Then use the implementation process to improve your data quality systematically.”

“Won’t that mean the schedule is wrong if the data is wrong?” Klaus asked.

“The schedule is already wrong,” Otto pointed out. “Sarah’s whiteboard is based on the same estimates from the same Business Central data. At least with scheduling software, we can see where the estimates are off and update them.”

Patrick nodded. “Otto’s right. The software will actually help us identify data problems. When a job consistently takes longer than scheduled, we’ll see the pattern and can update the standard time. Right now, that knowledge exists only in people’s heads.”

“So we’re not looking for software that works perfectly with perfect data,” Sarah said slowly. “We’re looking for software that works well enough with imperfect data and helps us improve that data over time.”

“Exactly,” Henning confirmed. “And that changes how you evaluate the vendors. Don’t focus on whose optimization algorithm is most sophisticated. Focus on whose system makes it easiest to work with reality versus theory.”

The Vendor Debrief

That afternoon, Sarah met with each vendor’s consultant to debrief their trial experience. The conversations were remarkably similar.

“Your Business Central data needs significant cleanup before we can generate reliable schedules,” the first consultant said.

“We can work with your data quality if you’re willing to manually review and adjust schedules daily,” the second consultant offered.

“Our system includes data quality tools that help identify inconsistencies,” the third consultant explained. “But you’ll need a dedicated effort to improve your master data accuracy.”

All three were technically correct. But only one—the third vendor—seemed to understand that data improvement was a journey, not a prerequisite.

Sarah made notes after each conversation, realizing that the trials had taught them something crucial: the software selection wasn’t just about features and capabilities. It was about finding a partner who understood the messy reality of SMB manufacturing and could help them improve gradually rather than demanding perfection up front.

The Path Forward

By Wednesday, the team reconvened to discuss their findings. The mood had shifted from excitement about new software to a realistic assessment of the work ahead.

“I’ll be honest,” Emma said. “I’m disappointed. I thought we’d select software, implement it, and solve our scheduling problems. Instead, we’ve discovered we have months of data cleanup work ahead of us.”

“But that’s not wasted effort,” Patrick countered. “We would have eventually hit these data quality issues whether we implemented scheduling software or not. At least now we’re discovering them proactively rather than through production failures.”

Sarah added, “And we’ve learned what matters in our data. Not everything needs to be perfectly accurate. We need good routing times for critical operations. We need accurate calendars showing real availability. We need to identify which operations are outsourced. But we don’t need to document every possible setup combination or capture every variable that affects production time.”

“So what’s our next step?” Klaus asked.

Emma looked at Henning on the video screen. “Henning, based on what we’ve learned, what do you recommend?”

“Two parallel tracks,” Henning replied. “First, select the scheduling software that best fits your situation—the one that can work with imperfect data while helping you improve it. Get that decision made so you’re not in perpetual evaluation mode. Second, start the data cleanup process with a clear priority list. Focus on the critical data that affects scheduling accuracy and worry about the rest later.”

“How long until we can actually use the software?” Emma asked.

“If you prioritize well, you could have a working schedule within four to eight weeks,” Henning said. “It won’t be perfect, but it will be better than your current whiteboard approach. Then you continue improving both the software usage and the data quality over the following months.”

Sarah felt relief wash over her. They weren’t looking at an impossible barrier—just a lot of hard work with a clear path forward.

The Evening Perspective

That evening, Sarah sat with Tom, helping him with a school project about problem-solving. He needed to describe a time when an initial solution didn’t work, and he had to try a different approach.

“What did you learn when your first idea didn’t work?” Sarah asked.

Tom thought about it. “I learned I didn’t really understand the problem as well as I thought I did.”

Sarah smiled. “That’s a very wise observation.”

“Is that what happened with your work problem?” Tom asked. “You thought you understood it, but then you learned more?”

“Exactly,” Sarah said. “We thought our problem was that we needed better scheduling software. But we learned our real problem is that we don’t have accurate enough data for any scheduling software to work well. So now we have to solve that problem first.”

“That sounds like a lot of work,” Tom observed.

“It is,” Sarah agreed. “But now we know what work needs to be done. That’s better than trying to fix the wrong problem.”

Miguel called from the kitchen. “Dinner in five minutes. And Sarah, don’t forget—you promised to come to Tom’s game Saturday.”

“Already on my calendar,” Sarah called back. “In fact, I blocked out the whole afternoon.”

Tom grinned. “With scheduling software?”

“With a much simpler system called ‘family time is non-negotiable,'” Sarah replied. “Some things are more important than production schedules.”

As they headed to dinner, Sarah realized that the data quality revelation, while uncomfortable, had been valuable. They now understood that successful scheduling required foundation work—not exciting or glamorous, but essential. Just like a good family dinner wasn’t about perfect planning, but about being present and committed.

Sometimes, the most important lesson was understanding what needed to be fixed before you could build something better.