Marcus Müller arrived at Alpine Precision Components on Thursday morning with the confident demeanor of someone who had seen these operational manufacturing challenges dozens of times before. Patrick met him in the lobby and escorted him to the conference room, where Emma, Klaus, Sarah, and Otto were already waiting.

“Thank you for coming on such short notice,” Emma said, shaking Marcus’s hand. “Patrick told you about our scheduling challenges and our need for working with a production scheduling consultant?”

“He gave me the overview,” Marcus replied, settling into a chair and opening his laptop. “Production scheduling gaps, whiteboard limitations, Business Central not handling finite capacity. Honestly, I see this situation at about half the manufacturers I work with.”

Sarah felt both relieved and slightly deflated by this comment. Relieved that they weren’t uniquely incompetent, but deflated that their problem was so common that consultants had a standard speech prepared.

Marcus pulled up a presentation on the conference room screen. “Let me start by explaining what I’ve observed across many Business Central manufacturing implementations. The ERP system excels at the ‘what’ and ‘how much’ of production—creating production orders, calculating material requirements, tracking costs, and managing inventory. But it leaves the ‘when’ and ‘in what sequence’ decisions entirely to human judgment and manual methods.”

Klaus nodded. “That’s exactly what we’ve discovered. Business Central tells us what needs to be made, but not how actually to make it happen with our finite resources.”

“Right,” Marcus continued. “This gap is particularly common in mid-market manufacturing companies. You’ve successfully digitized your transactional processes—sales orders, purchase orders, invoicing, and financial reporting. But you’re still using industrial-age methods for your most critical operational decisions.”

He clicked to the next slide, which showed a diagram of typical manufacturing software categories. “Now, when it comes to filling this gap, there are several approaches. You can implement standalone scheduling software that connects to Business Central via custom interfaces. You can use Business Central’s standard production module with manual scheduling support. Or you can look at integrated solutions specifically designed for environments like yours.”

Finding a Production Scheduling Consultant

Emma leaned forward. “Patrick mentioned you have experience with Business Central, but scheduling itself is quite specialized. Do you personally have expertise in production scheduling for high-mix, low-volume environments like ours?”

Marcus smiled, and Sarah noticed a flicker of something—respect? relief?—cross his face. “That’s an excellent question, and I appreciate your directness. I know Business Central manufacturing inside and out. I can tell you exactly how the MRP logic works, how production orders flow through the system, and how to configure master data for optimal ERP performance. But production scheduling—particularly for job shops like yours—is its own discipline.”

He closed his laptop and looked around the table. “I’ve implemented scheduling solutions before, but I’m honest enough to know that I don’t have the deep expertise in scheduling theory and practice that a company like yours needs. You need someone who understands not just the software, but the operational realities of high-mix, low-volume manufacturing.”

Sarah found herself warming to Marcus. Many other ERP consultants would have oversold their capabilities, but he was being refreshingly honest about his limitations.

“So what do you recommend?” Klaus asked.

“I recommend bringing in a production scheduling consultant and specialist to work alongside me,” Marcus said. “Someone who combines deep scheduling knowledge with an understanding of how the ERP systems work. I know Business Central’s technical architecture and data structures. A production scheduling consultant and expert knows how to translate shop floor reality into productive scheduling approaches. Together, we can help you find a solution that works.”

Patrick was already making notes. “Do you know someone who fits that profile?”

Marcus nodded. “Actually, I do. Henning Karlsen. He’s been working with production scheduling for over twenty-five years, with a specific focus on small and medium-sized manufacturers. He understands Business Central manufacturing, though he’s not an ERP consultant himself. His background is more operational—he’s worked in production management, implemented scheduling systems, and has a very pragmatic approach.”

“Pragmatic is exactly what we need,” Emma said. “Can you reach out to him?”

“I already did, anticipating you might want to bring in additional expertise,” Marcus said with a slight smile. “He’s available for a call this afternoon if you’d like to meet him virtually first.”

The First Assessment

That afternoon, the team reconvened for a video call with Henning Karlsen. The screen showed a man in his early fifties with graying hair and the kind of relaxed confidence that came from decades of practical experience.

“Thank you for taking the time,” Emma began. “Marcus has explained our situation, but I’d like to hear your initial thoughts after learning about our challenges.”

Henning leaned back in his chair. “From what Marcus described, your situation isn’t unusual, but it’s also not simple. You’ve grown from a small shop where informal coordination worked into a more complex operation where those old methods are breaking down. That’s a critical transition point.”

He pulled up a document on his screen. “May I ask a few questions to understand your specific situation better?”

“Of course,” Sarah replied.

“First, when you schedule production now with your whiteboard, are you scheduling just machines, or machines and people?”

Sarah thought about this carefully. “Primarily machines. We assign jobs to specific machines and assume the operators will be available. Though Otto often has to juggle operator assignments when reality doesn’t match our assumptions.”

“That’s common,” Henning said, making notes. “Second question: Do you have clear bottleneck machines, or does your bottleneck shift depending on what’s in your order backlog?”

Klaus answered this one. “It shifts. We’re a job shop with high-mix, low-volume production. Depending on the mix of orders, different machines become bottlenecks at different times.”

“Excellent,” Henning said. “That’s actually a key distinction. You’re not like a traditional manufacturing plant with one permanent bottleneck. Your constraints are dynamic.” He paused. “Third question: When you think about what you need from scheduling software, what comes to mind? Optimization of machine utilization? Minimizing setup times? Ensuring on-time delivery? Something else?”

Sarah had been thinking about this since last weekend’s scheduling nightmare. “Visibility and control. I need to see what happens when things change. Last weekend, when I tried to accommodate an expedited order, I couldn’t manually track all the ripple effects. I need to understand the consequences of my decisions quickly enough to actually make good decisions.”

Henning smiled. “That’s the most honest answer I’ve heard in a long time. Most people tell me they need ‘optimization’ without really understanding what that means or whether it’s even achievable in their environment.”

The Uncomfortable Truth

“Let me share something that might be uncomfortable to hear,” Henning continued. “In high-mix, low-volume environments like yours, true mathematical optimization is often neither practical nor desirable.”

Klaus frowned. “What do you mean? Isn’t the point of scheduling software to optimize our production?”

“That depends on what you mean by optimize our production,” Henning replied. “I’m sure your answer here will be different from that of many of your colleagues. If I ask Otto what an optimal schedule looks like, he’ll aim for the highest possible utilization of his machines and the lowest possible setup costs. If, on the other hand, I ask salespeople, the answer will almost certainly be ‘on-time delivery’.

Emma, to add another stakeholder to that equation, will undoubtedly want the schedule that maximizes her EBITDA. Even if we abstract from this issue for a moment and assume that scheduling only deals directly with the time aspect, not with the associated costs and revenues, we immediately come across the next major problem in your use case. “

“And this is which one?”, Sarah asked, feeling a bit overwhelmed by the many variations of a schedule’s purpose that Henning had just thrown up in the blink of an eye.

“True optimization”, Henning continued, “requires extraordinarily stable, accurate data. Your routing times need to be precise. Your setup sequences need to be predictable. Your material availability needs to be certain. But in a job shop environment, those things are inherently variable. Your routing time for a bearing housing operation might be fifteen minutes on average, but it varies based on dozens of factors—which operator is running it, what the previous job was, whether the tooling is already mounted, if there are any quality concerns, and most likely much more.”

He pulled up a simple diagram. “If you feed an optimization algorithm data that has inherent variability, you get garbage in, garbage out. The algorithm will calculate a mathematically perfect schedule based on your current estimated input, but that schedule won’t survive contact with reality. Optimization approaches only give you the illusion of a precise optimum, which does not exist in your shop floor reality. “

Sarah found herself nodding vigorously. This matched exactly what she’d experienced last weekend.

“So what’s the alternative?” Patrick asked.

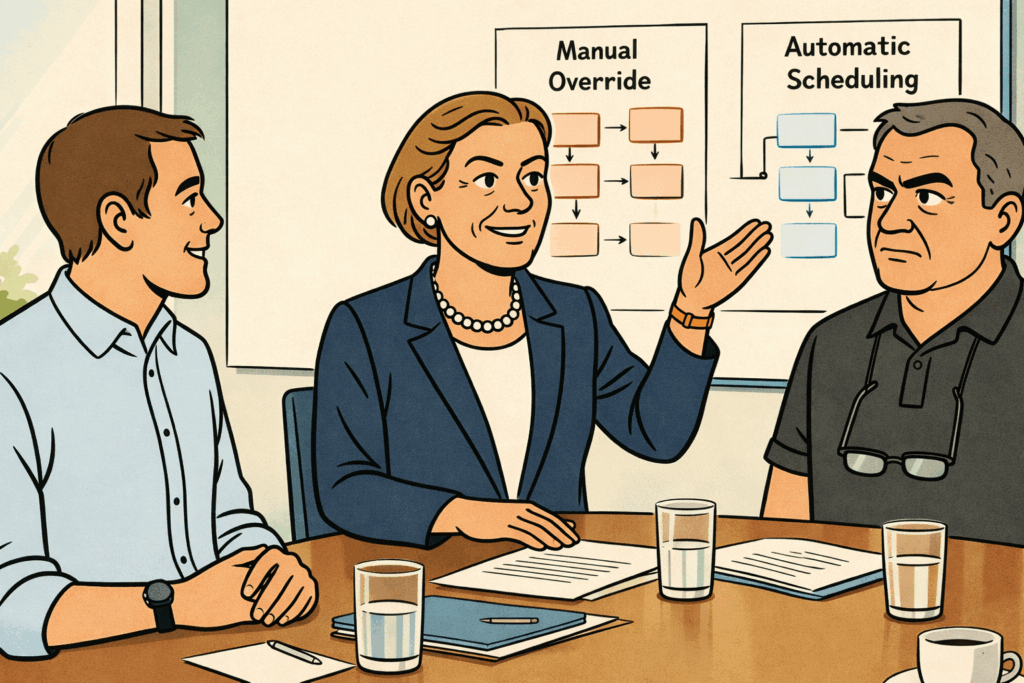

“Pragmatic scheduling to gain transparency and reliable results instead of chasing the optimum in vain,” Henning said. “Scheduling software that helps you create feasible sequences quickly, see conflicts clearly, and adapt rapidly when reality differs from your plan. Software that amplifies human judgment rather than trying to replace it.”

Otto spoke up from his corner of the table. “That sounds more like what we actually need. I don’t need a computer to tell me the perfect schedule. I need a computer that helps me see what’s happening and make good decisions.”

“Exactly,” Henning said. “And that’s particularly important in your environment, where bottlenecks shift. You need software that helps you identify where your current bottleneck is and make informed decisions about how to manage it. Not software that pretends to know the optimal solution based on volatile data.”

The Reality Check

Emma had been listening intently. “Henning, this is helpful, but I want to understand something. We’ve just come through a quarter where we posted our first negative EBITDA in thirty-eight years. We need solutions that work now, not theoretical discussions about optimization versus good-enough scheduling. Can you help us?”

Henning’s expression grew serious. “I appreciate your directness, Emma. Yes, I am confident I can help, but only if we’re realistic about what ‘help’ means. I can’t give you software that magically solves all your problems. What I can do is help you find practical scheduling tools that work with your current reality—your current data quality, your current processes, your current team capabilities—and then help you improve over time.”

He leaned forward. “Here’s what I’ve learned after twenty-five years: successful scheduling implementations are about twenty percent software and eighty percent process improvement, data cleanup, and organizational change. The companies that succeed are the ones willing to do that work. The companies that fail are the ones looking for a software silver bullet.”

Sarah glanced at Emma, wondering if Henning’s honesty might have crossed a line. But Emma was nodding thoughtfully.

“I’d rather hear hard truths now than false promises that fall apart later,” Emma said. “If you’re willing to help us do this the right way, I’d like to engage you to work with Marcus on this project.”

“I’m willing,” Henning said. “But I have one condition. I need full access to your shop floor, not just your conference rooms. I need to spend time with Sarah understanding how she actually schedules today. I need to walk the floor with Otto and understand what really happens versus what the systems say happens. I need to see the reality, not just the data.”

“Done,” Emma said immediately. “When can you start?”

“I can be there next Tuesday for a full-day assessment. Marcus and I can coordinate on the technical ERP aspects, and I’ll focus on the operational scheduling requirements. After that, we’ll present you with options—not just software options, but process options and implementation approaches.”

The Next Steps

After the call ended, the team sat in silence for a moment, processing what they’d just heard.

“Well,” Klaus said finally, “that was refreshingly honest. Almost brutally so.”

“That’s exactly what we need,” Emma replied. “We’ve spent too long pretending our problems are simpler than they are. Henning is telling us the truth, even when it’s uncomfortable.”

Sarah was making notes in her notebook, her mind already racing ahead to what she needed to prepare for Henning’s visit. “He’s right about the data quality issue. If we’re going to evaluate scheduling software properly, we need to be honest about what our data really looks like versus what we wish it looked like.”

Patrick nodded. “I’ll work with Marcus on the technical integration aspects. We need to understand what data Business Central can provide for any scheduling software and how that data flows back and forth.”

Otto cleared his throat. “I like this Henning fellow. He talks like someone who’s actually worked on a shop floor, not just read about it in textbooks.”

“That’s high praise coming from you,” Emma said with a smile. “Alright, here’s what we need to do before Henning arrives next Tuesday. Sarah, I want you to document your current scheduling process in detail. Not how it’s supposed to work, but how it actually works. Every step, every decision point, every workaround.”

“I can do that,” Sarah said.

“Klaus, I want you to identify three or four recent scheduling challenges—situations where the whiteboard approach didn’t work well. Specific examples with real data that Henning can analyze.”

“The Agrar-Tech expedite from last week would be perfect,” Klaus replied.

“Patrick, work with Marcus on understanding the technical integration options. What data does Business Central have, what data do we wish it had, and what data we’ll need to collect manually.”

Emma looked around the table. “We have one week to prepare for this assessment. Let’s make sure we give Henning and Marcus everything they need to help us make the right decisions.”

A Quiet Moment

That evening, Sarah sat at her kitchen table with a blank notebook, trying to document her scheduling process as Emma had requested. Tom was doing homework across from her, occasionally asking questions about math problems. Miguel was cooking dinner, the comforting sounds and smells of their evening routine providing a backdrop to her work.

“Mom,” Tom said, looking up from his worksheet, “how do you decide what order to do things in when you have a lot of stuff to do?”

Sarah smiled at the question’s perfect timing. “What do you mean, sweetie?”

“Like, I have homework in three subjects tonight. How do I decide which to do first?”

Sarah thought about this. “Well, what do you usually think about?”

“Which one is due first. Which one is hardest. Which one I like least, so I can get it over with.”

“Those are all good factors,” Sarah said. “You’re thinking about deadlines, difficulty, and personal preference. That’s actually a lot like what I do at work, just with more complicated variables.”

“Does your new computer program help you decide?”

Sarah paused. They hadn’t selected any software yet, but Tom’s question crystallized something important. “We don’t have the new program yet. But what I’ve learned is that the computer can’t make the decision without my involvement. It can help me see what happens with different choices, but I still have to decide based on all the things I know that the computer doesn’t.”

Tom nodded, apparently satisfied, and returned to his homework. He chose to start with mathematics—his hardest subject—to get it over with first. Sarah watched him work, thinking about how even a ten-year-old understood that decision-making is a complex process that requires consideration of various factors.

Her phone buzzed with a text from Miguel: “Dinner in 10. You look like you’re having a breakthrough?”

She looked up to find him watching her with a knowing smile.

“Maybe,” she typed back. “Or maybe I’m just learning to ask the right questions.”

As she returned to documenting her scheduling process, Sarah realized that this was the first evening in weeks when she’d been working on a problem that felt solvable. Not easy, not quick, but solvable. They had experts coming to help. They had management commitment. They had a realistic assessment of their challenges.

For the first time since the whiteboard had struck back, she felt like they might actually figure out what came next.