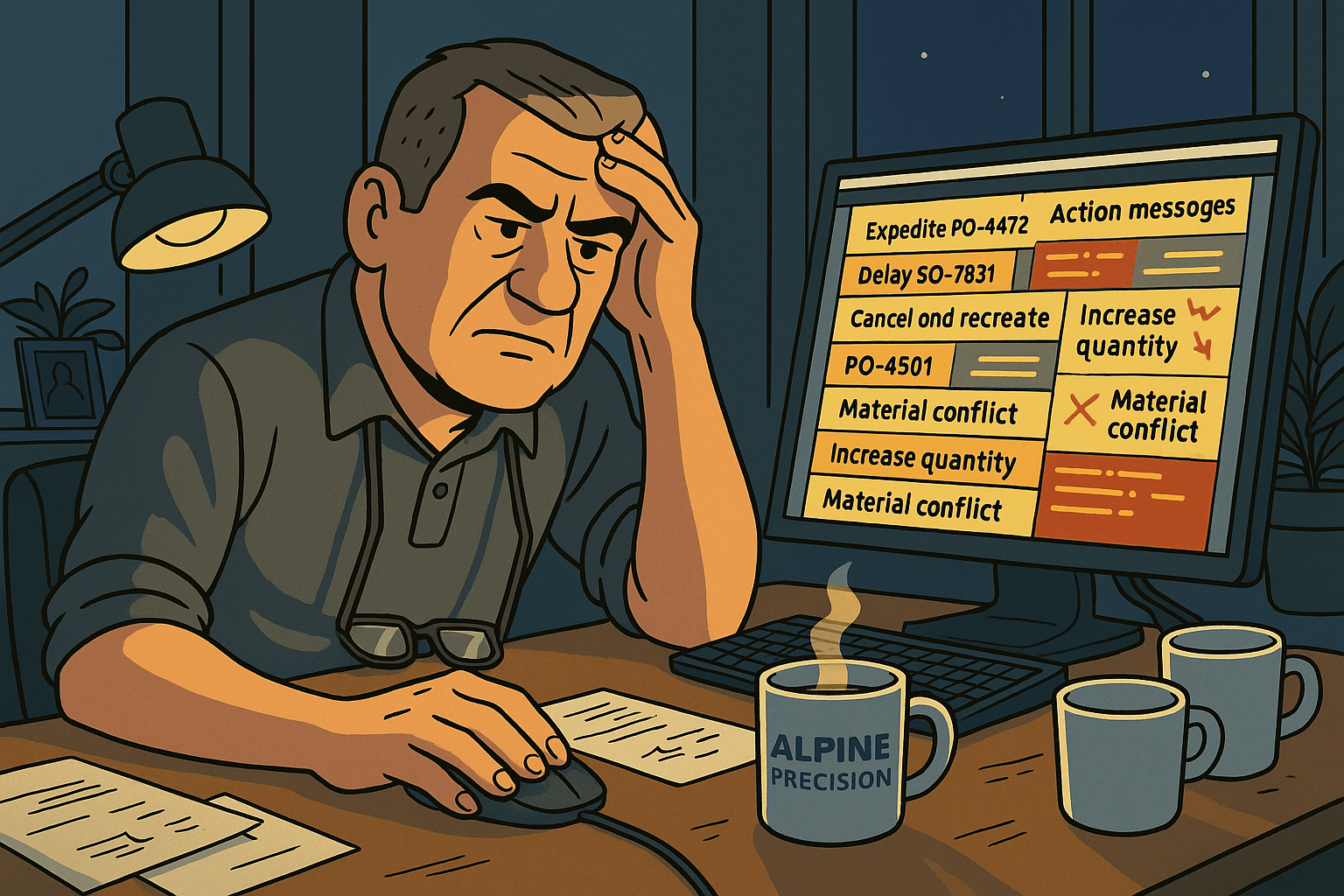

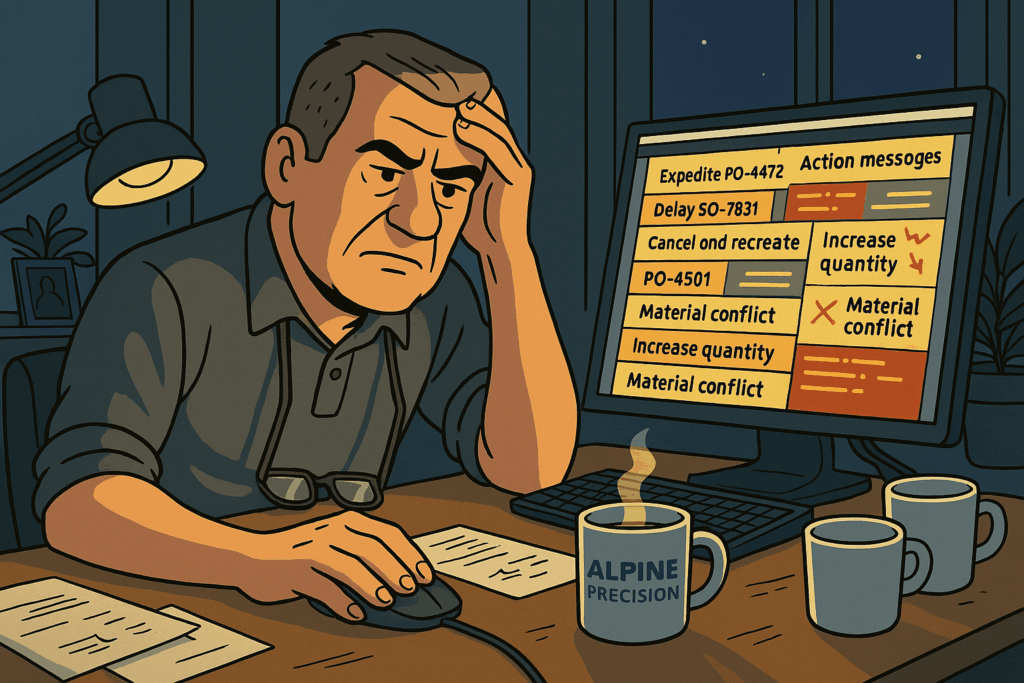

Tuesday morning found Klaus Brenner in his office at 6:30 AM, two hours before the official workday began, staring at his computer screen with the kind of grim determination usually reserved for studying autopsy reports. The Business Central planning worksheet was open, displaying what Microsoft cheerfully called “action messages”—hundreds of lines in a super sophisticated table suggesting he cancel orders, create new orders, expedite orders, delay deliveries, increase quantities, reduce quantities, and generally reorganize Alpine’s entire purchase and production backlog based on the system’s overnight calculations.

He took a long sip of his coffee—his third cup already—and started working through the list. Expedite production order PO-4472. Delay sales order SO-7831. Increase purchase order quantity for bearing assemblies. Cancel and recreate production order PO-4501 due to material availability conflicts.

And he knew it: Accepting those action messages would trigger new action messages when running the next regenerative plan. Expediting one order created conflicts with three others. Delaying a sales order freed up capacity that the system immediately wanted to fill with different work. It was like playing whack-a-mole with mathematical precision, and Klaus was losing.

The Action Messages Mess

Klaus stared at the screen full of action messages that seemed to multiply even as he worked through them. The ERP system apparently thought Tuesday morning was the perfect time to suggest reorganizing their entire manufacturing strategy.

By 7:15, he’d processed thirty-seven action messages and somehow created twenty-two new ones. The system’s logic was impeccable, but its suggestions were becoming increasingly divorced from reality. Expedite an order that couldn’t start because the required material shipment from their supplier was delayed. Delay a delivery for a customer who’d specifically requested an early shipment. Increase a purchase quantity for materials they were already overstocked on.

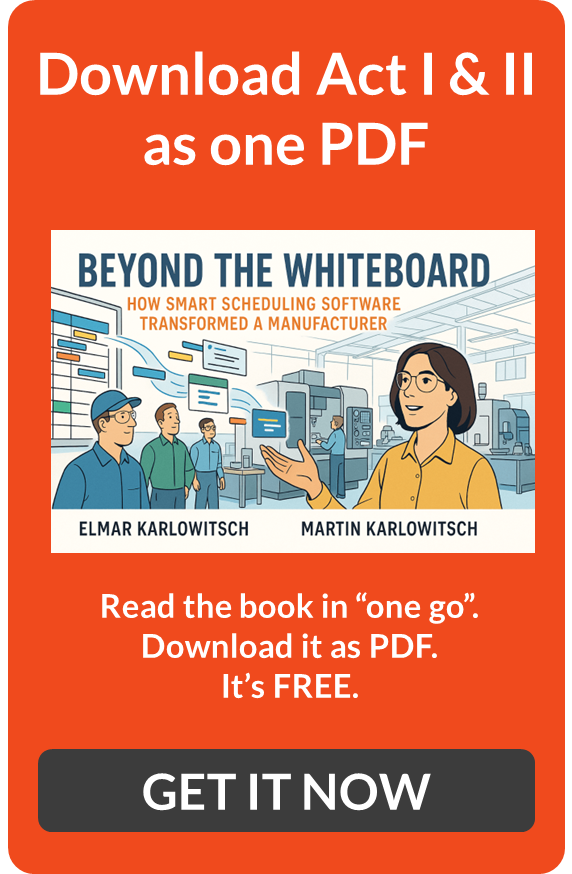

“This is ridiculous,” he muttered, reaching for his phone to call Patrick.

“Klaus?” Patrick answered on the first ring. “Please tell me you’re not calling about the planning worksheet.”

“I’m calling about the planning worksheet,” Klaus said grimly. “It’s trying to get me to delay the Brenner Industries order—you know, the one that’s already caused us problems with Mazak #3 being down?”

“The system doesn’t know about that machine being down,” Patrick said carefully. “You’d need to update the respective machine center calendar to reflect that.”

“I did update it. Yesterday afternoon.”

There was a pause. “What exactly did you do?”

Klaus looked at his screen. “I set the capacity to zero.”

“OK interesting approach. Not as designed by the system, but interesting. Anyway, I suppose that you did not apply the changed calendar settings. Or did you hit ‘calculate machine center’ afterwards?”

“Now I am lost. Cannot remember that this was part of the super user training”, said Klaus and felt a familiar surge of frustration. “Patrick, why does a system that’s supposed to help manage production require a computer science degree to operate?”

“It doesn’t require a computer science degree,” Patrick said, though his defensive tone suggested he’d had this conversation before. “It just requires understanding of how the system works. Business Central is incredibly powerful—it can handle complex manufacturing scenarios that would be impossible to manage manually.”

“Then why,” Klaus asked, scrolling through the next layer of action messages, “is it suggesting I start production last week Thursday?”

Another pause. “What’s the order number?”

Klaus squinted at the screen. “PO-4489. Agricultural component batch.”

He could hear Patrick typing. “Ah, I see the issue. The demand date is today. Someone in sales was dreaming when they created the sales order. The system uses the demand date, and calculates the production order backwards. And if I look at the routing time, you should have started last week to deliver today. The MRP logic is exactly doing what it is supposed to do.”

“Well, if that logic tells me today that I should have started production last week, can I use that same logic also to predict next week’s lottery numbers? How can I reliably and efficiently work with that kind of logic?”

The Infinite Capacity Assumption

“You should stop being cynical and focus your energy on understanding the logic. The logic is clear—although you might not like it. It starts from the demand date.”

Klaus closed his eyes and rubbed his temples. “So, you are telling me that I need to update the demand date in the sales order first? Looking forward to the faces of our beloved sales team when I mess around with their dates.”

“Well, that’s another point. The point that I am making is the following: You need to understand which information drives which process. The beauty of Business Central is its flexibility—you can handle exceptions without changing your master data, or you can update your master data to reflect new reality. This is super powerful.”

“Patrick, it’s 7:30 in the morning. I haven’t had breakfast yet. And you’re asking me to become a database philosopher to figure out whether I should expect the logic to deliver meaningful results, or whether I should mess around with demand dates on sales orders.”

Klaus heard Patrick sigh. “Look, why don’t I come down and walk through this with you?”

Twenty minutes later, Patrick appeared in Klaus’s office with his laptop and the patient expression of someone about to explain quantum physics to a particularly stubborn high school student.

“The thing you need to understand about Business Central,” Patrick said, settling into a chair, “is that it’s designed to handle every possible manufacturing scenario. Make-to-stock, make-to-order, assemble-to-order, engineer-to-order. Job shops, flow manufacturing, process industries. The flexibility is incredible.”

“I don’t want incredible flexibility,” Klaus said. “I want to know whether I can deliver the Brenner Industries order on Friday.”

Patrick opened his laptop and connected it to Klaus’s external monitor. “Okay, let’s look at that specific order.”

The screen filled with dozens of pages and views drilling into aspects of the complex issue—production orders, material requirements, capacity calculations, and routing dependencies. Patrick began clicking through various screens, each one revealing new layers of information.

“See, here’s your production order for the Brenner housings,” Patrick said, pointing to a line item. “And here’s the routing that shows it needs to go through machining, heat treatment, and final assembly plus the estimated lead times of each operation. The system calculates backward from your promised delivery date to determine when each operation needs to start.”

“That’s what I expected it to do,” Klaus said. “So why is it telling me the order is already late when we haven’t even started it?”

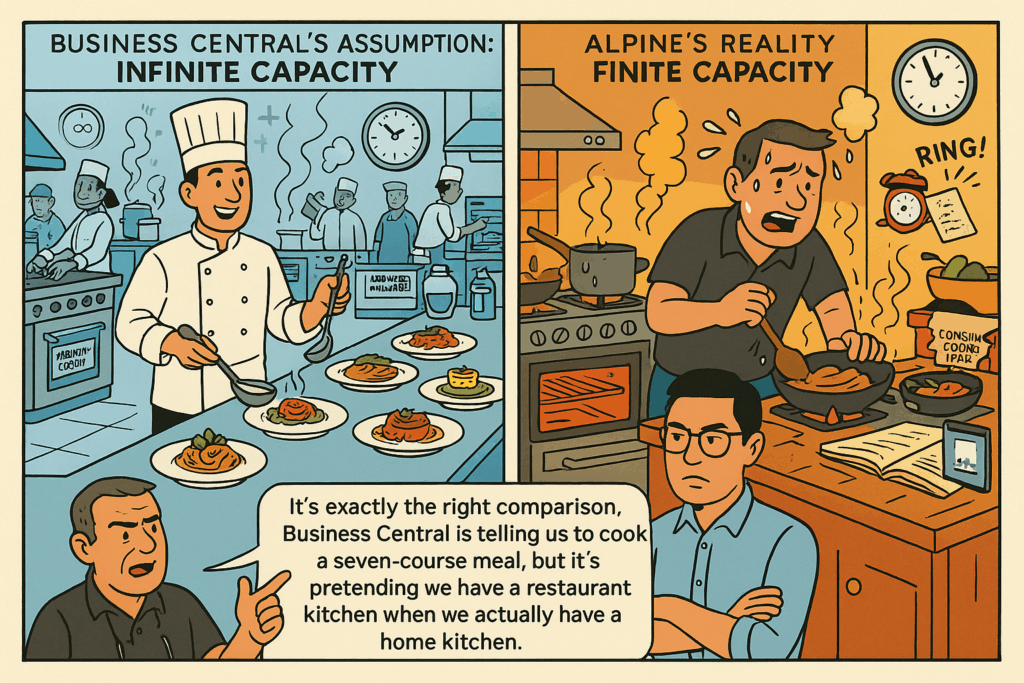

Patrick clicked to another screen. “Because the system assumes infinite capacity. It calculates when operations should start based on your routing times, but it doesn’t consider whether the machines or people are actually available.”

Klaus stared at the screen. “It assumes infinite capacity?”

“Right. Think of it as the difference between a theoretical schedule and a realistic schedule. Business Central creates the theoretical schedule—what would happen if you had unlimited resources. Then it’s up to you to figure out how to make that work with your actual resources.”

“But we bought Business Central specifically to help with production scheduling.”

MRP vs. Finite Capacity Scheduling

“We bought Business Central to help with production planning,” Patrick corrected. “Planning and scheduling are different things. Planning is determining what to make and when to make it based on demand and material availability. Scheduling is determining the specific sequence of operations based on finite capacity constraints.”

Klaus felt something cold settling in his stomach. “Are you telling me that our brand-new, super modern, cloud-based ERP system with agentic AI around the corner doesn’t actually do production scheduling?”

Patrick shifted uncomfortably. “It does backward scheduling based on routing times, the shop calendar, and due dates. It just doesn’t do finite capacity scheduling.”

“What’s the difference?”

“Finite capacity scheduling considers the actual availability of machines and people. It knows that machine Mazak #3 is down for maintenance, or that your best CNC operator is on vacation, or that you can’t run two setup-intensive jobs on the same machine simultaneously.”

Klaus looked at his computer screen, then at Patrick, then back at the screen. “So when I look at this production schedule that Business Central has created, it’s basically fiction?”

“It’s not fiction,” Patrick protested. “It’s a starting point. It’s infinite capacity planning. It tells you what needs to happen and by when. What you need is finite capacity scheduling to make it realistic. This is what happens when you and Sarah figure out how to sequence the orders with your actual resources.”

“Using the whiteboard.”

“Using whatever method works for you to consider the given finite capacity.”

Klaus stood up and walked to the window overlooking the shop floor. Below, he could see the familiar scene of organized activity—workers moving between machines, supervisors checking on progress, materials being transported from station to station. It looked productive and purposeful, but after yesterday’s meeting about negative EBITDA, he was beginning to question whether appearances were deceiving.

The Dinner Party Analogy

“Patrick, let me ask you something. If you were trying to plan a dinner party for fifty people, would you use a system that told you what dishes to prepare and when to start cooking them, but ignored the fact that you only have four burners on your stove?”

“That’s not really a fair comparison—”

“It’s exactly the right comparison,” Klaus interrupted. “Business Central is telling us to cook a seven-course meal, but it’s pretending we have a restaurant kitchen when we actually have a home kitchen. And then it’s surprised when we can’t deliver on time.”

Patrick closed his laptop with a slight snap. “Klaus, Business Central is working exactly as designed. It’s handling our financial management, inventory control, purchase ordering, sales processing, and production planning better than any system we’ve ever had. The fact that it doesn’t do finite capacity scheduling doesn’t mean it’s broken.”

“No,” Klaus said, still looking out at the shop floor, “but it means we’ve been expecting it to solve a problem it wasn’t designed to solve. Patrick, I appreciate you coming down to explain this. But I think we need to have a different conversation.”

“What kind of conversation?”

“The kind where we admit that having a world-class transaction processing system doesn’t necessarily give us world-class production control with visibility into the real shop floor situation over the planning horizon.”

Patrick gathered his things. “What are you suggesting?”

The Whiteboard as Finite Capacity Scheduling Island

Klaus thought about Sarah’s whiteboard, about the invisible complexity Otto had described, about the financial crisis Emma had revealed yesterday. “I’m suggesting that maybe we’ve been asking the wrong question. Instead of asking why Business Central can’t do finite capacity scheduling, maybe we should be asking what we need to do finite capacity scheduling properly.”

“That sounds like a conversation for the management meeting this afternoon.”

Klaus checked his watch. 8:45 AM. He’d spent two hours wrestling with the planning worksheet and had barely made a dent in the action messages. Meanwhile, somewhere in the building, Sarah was probably standing in front of her whiteboard trying to figure out how to turn Business Central’s infinite capacity assumptions into a workable production schedule.

“Patrick, one more question. If Business Central assumes infinite capacity, how does Sarah’s scheduling work fit with what the system is telling us?”

Patrick paused at the door. “It doesn’t, really. Sarah’s schedule is based on finite capacity reality. Business Central’s schedule is based on infinite capacity theory. She’s basically translating between two different languages.”

“And when they conflict?”

“Sarah wins. She has to. You can’t ship theoretical products to real customers.”

After Patrick left, Klaus sat back down at his computer and stared at the action messages that continued to blink cheerfully at him. Each message represented the system’s best guess about what should happen in an ideal world. But Alpine didn’t operate in a perfect world. They operated in a world where machines broke down, materials arrived late, workers got sick, and customers changed their minds.

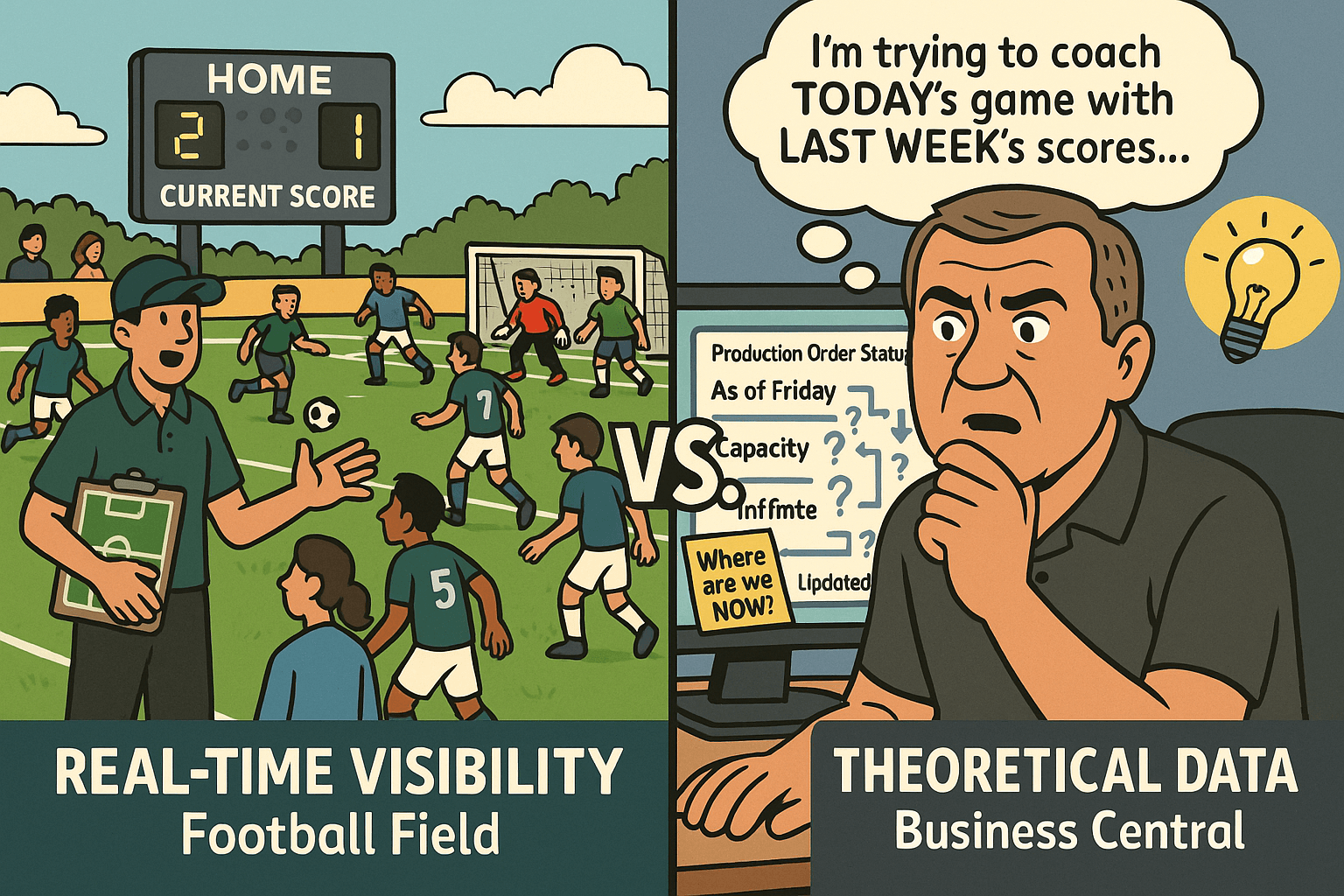

He thought about the call he had with Sarah last night and her description of Tom’s soccer game yesterday—how everyone could see exactly what was happening in real-time. The scoreboard showed the current score, not last week’s results. The players could see where their teammates were positioned, not where they were supposed to be according to the coach’s pre-game match plan or according to their theoretical 4-3-3 formation. The coaches could make tactical adjustments based on what was actually unfolding on the field.

But here he was, staring at a computer screen that was essentially showing him last week’s soccer scores while expecting him to coach today’s game. Business Central’s infinite capacity schedule was like trying to manage a live match using yesterday’s game plan, without knowing which players were actually on the field or whether the opposing team had changed their strategy.

More Reality Checks

The irony was almost painful. They’d invested in Business Central to bring sophistication and precision to their manufacturing operation. And it had delivered exactly that—for everything except the most critical operational decision they made every day: what to work on next.

His phone rang. Sarah’s extension.

“Klaus, I’m looking at the production orders that came out of your MRP run, and I have some questions.”

“Let me guess. The system wants us to start jobs before we have materials, expedite orders that can’t be expedited, and delay deliveries that can’t be delayed?”

“That’s… actually a pretty good summary. Are you getting a better understanding of what I deal with every morning?”

Klaus looked at his screen one more time, then closed the planning worksheet. “Sarah, I think I owe you an apology. I’ve been expecting you to make Business Central’s theoretical schedules work in the real world with your mighty whiteboard, without understanding that the ERP system wasn’t designed to handle real-world constraints.”

“Does this mean you’re ready to have that conversation about what comes after the whiteboard?”

Klaus thought about his morning struggle with action messages, about Patrick’s explanations of infinite capacity assumptions, about the gap between transaction systems and production control systems. “I think I’m ready to admit that the whiteboard isn’t the problem. The problem is that we’ve outgrown the whiteboard without replacing it with something that actually works better.”

“Emma’s called another meeting for this afternoon. Want me to put this on the agenda?”

Klaus looked at his watch again. He had the rest of the morning to deal with production issues, a meeting this afternoon, and a growing suspicion that Alpine’s ERP honeymoon was officially over.

“Put it on the agenda,” he said. “It’s time we figured out what Business Central can and can’t do for us. And more importantly, what we’re going to do about the things it can’t do.”